By David M. Greenwald

Executive Editor

Davis, CA – Opponents to housing in Davis have a proven formula for winning Measure J elections. Since 2005, just two Measure J projects have passed while five have been defeated.

That track record probably masks the true impact of Measure J, in part because of the deterrence effect of the measure and the fact that over the last 25 years the city of Davis has actually built just over 700 single-family homes.

There are reasons to believe that the community should be more receptive to housing. For one thing, polling has shown in recent years that the vast majority of residents seemingly understand that the cost of housing is one of the largest problems in Davis.

But that has not translated into approvals for Measure J projects necessarily.

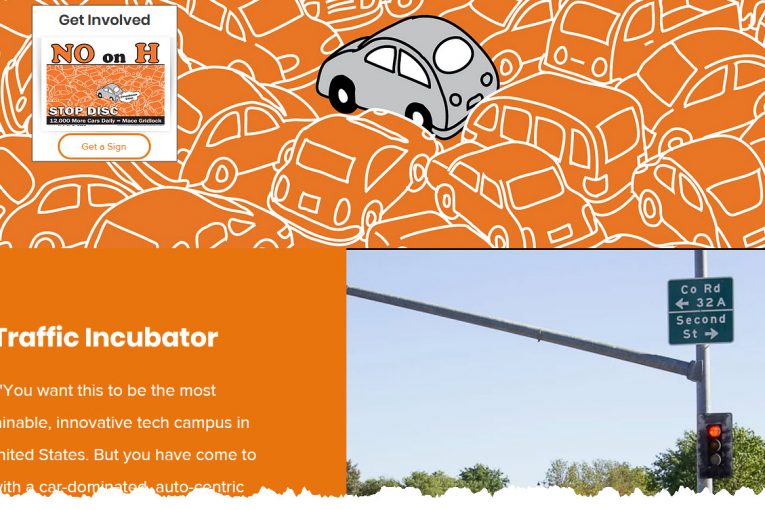

Probably the most effective tool that opponents have is scare tactics for traffic impacts. It is noteworthy that the two projects that passed Measure J votes either had perceived minimal traffic impacts (West Davis Active Adult Community) or took traffic off the table—Nishi—by limiting access to Richards Blvd.

In the first project to get voted down, Covell Village, the key factor was traffic impacts on Pole Line and Covell.

The most recent project—DISC both in 2020 and 2022—the campaigns focused on congestion along the Mace Corridor.

And, as we saw this weekend, the opposition to Village Farms is leading with traffic.

“Massive traffic” is the lead. “Traffic Congestion,” it explains going back to the 2005 Covell Village proposal which traffic analysis said would “almost double traffic” with “39,440 cars per day” and Pole  Line would more than double to 26,900 cars per day.”

Line would more than double to 26,900 cars per day.”

The reality is that pretty much every peripheral proposal is likely to create traffic impacts.

The city has a housing crisis that mirrors that of the state. And the state is asking the city to plan for 2075 units this RHNA cycle and the city is estimating another 4000 or more units in the next RHNA cycle.

“The city in a nutshell is going to have to turn over every stone of infill sites, but even that alone will not do it. We are going to, I think without question, also need to be looking very seriously at periphery housing sites as well,” City Manager Mike Webb acknowledged at the last council meeting.

The question is how can they fend off scare tactics like traffic to convince citizens to build more housing?

That’s been the problem of Measure J for a long time.

We know what doesn’t work. Proponents of DISC attempted to get overly aggressive and fought back against what they regarded as false and misleading ballot arguments through litigation. That approach massively backfired. Not only did the project lose by a greater than 60-40 margin, but the councilmember who led the way was voted out of office six months later.

On the other hand, sitting back and allowing the project to get hammered by scare tactics and misinformation doesn’t work either. There were several times when the issues were already framed by the opposition before proponents even got organized.

So what can supporters of housing do?

First, there needs to be an early and aggressive education campaign by key stakeholders.

Several key points need to be raised:

- State mandates on housing

- The local situation as far as costs and availability of housing

- A discussion on where housing can go, availability of infill, and need for peripheral housing

- Housing needs also need to be tied into schools and declining enrollment and its impact on school quality and finances

The second key thing that needs to happen is an aggressive early outreach to neighbors and other key stakeholders. To the extent possible, the developers should meet with as many people as possible, starting with neighbors and extending to key stakeholders.

While it is true that Measure J elections are citywide, localized effects matter. In the 2020 DISC election we saw the measure defeated by the overwhelming opposition of those closest to the project. The opposition declined as one moved away from the project and those on the other side of town at least modestly supported the project.

There is also the example of Trackside versus Lincoln40. While not Measure J votes, Trackside incurred large amounts of opposition from the neighbors and the relations were poisoned by the first proposal and early interactions.

On the other hand, Lincoln40 worked closely with the adjacent neighborhood and headed off most of the opposition from neighbors.

West Davis is another example of proactive outreach that was able to anticipate and address as many of the points of contention as possible enabling the project to pass a Measure J vote.

It is noteworthy how strong the salience of perceived traffic impacts actually is. Nishi in 2016 attempted to solve the perceived problems on Richards Blvd, and the developer was willing to pump in about $10 million as part of a corridor plan to help divert some of the traffic from the underpass directly to campus—the community still didn’t support the project.

Can a concerted education campaign work to lessen opposition? That’s a big a question that has not been answered. So far, the only two projects to pass Measure J votes were projects that did not seem to have big traffic impacts. It’s difficult to imagine that any of the five peripheral projects won’t have concerns about traffic.

Traffic mitigation measures have not succeeded in alleviating that concern enough to allow for passage of projects.

Could a message be: the state is requiring us to build additional housing, some of that housing is going to have to require a vote of the people, we will do our best to attempt to mitigate additional traffic impacts, but we likely can’t reduce them to zero—will that work? Hard to know.

The alternative is that at some point the state or another entity could move to take out Measure J protections—which for many in the community might be an even worse outcome.

David, you are falling into the trap of painting with far too broad a brush when you lump all the Measure J projects together.

The two DiSC projects were industrial/innovation parks, not residential developments. Their fatal flaw, which the opponents of those projects very clearly highlighted was that they were (1) very poorly planned, (2) had no clear financial win for the community, and (3) were not endorsed by UCD

Equating Covell Village with either Wildhorse Ranch or WDAAC is just plain stupid. Covell Village was huge. Both of the others were very modest in size. Wildhorse Ranch was extremely poorly planned, while WDAAC was actually pretty well planned. Wildhorse Ranch had no illegal buyers program, while WDAAC did. Wildhorse Ranch had a terrible plan for its election campaign. WDAAC had a well thought out and well researched election campaign.

Nishi 2016 was inadequately planned (no traffic plan and no affordable housing component).

Nishi 2018 was much better planned (traffic was addressed and an affordable housing plan was added).

You are on a fool’s errand when you try and lump them all together into a single group. The devil is in the details.

I think the way to “overcome” the objections of anti-development crowd is to LISTEN to them, take their objections seriously, and adress their concerns.

To be sure, some of the concerns are scare tactics, and some are willfully ignorant, like assuming that NOT building at Pole line isnt going to just mean more people coming DOWN pole-line from spring lake.

But the way to overcome these issues is to do it with mitigation for the valid concerns and with truth for the lies.

To me, the biggest failure of the DiSC campaign, besides the lawsuit coming from Dan Carson was the vapid campaign and its stupid lawnsigns… talking about parks, and bikepaths etc… a clumsy and transparent attempt at greenwashing that everyone saw right through, all while simply ignoring all of the really valid reasons why we need to build more innovation space.

The approach to housing that I am championing is VERY MUCH tied around this objection to traffic, because we all share in the negative downtisdes of traffic, INCLUDING the un-necessary tailpipe emissions of people as they commute in to town to their jobs.

Now Davd, you really do need to stop measuing success in housing around number of single family homes… we shouldn’t be building very many single family homes at all because every single family home comes with at least two cars on our roads. Its an out-dated, irresponsible, and un-sustainable way to think about cities. Like hunting whaling and coal power plants, and logging old growth timber…

My approach to housing as discussed yesterday is about focusing squarely on providing in-town housing for people who are already coming here anyway. Transit-connected, limited parking, missing middle housing is how we do that. If we build our cities trying to max out the Rubric… we will do fine. ( the rubric comparing two single family developments is a joke… but the rubric comparing missing-middle transit-connected housing WILL show clear superiority.

Building single family homes is building FOR traffic problems. The opposition is 100% correct about that.

Now, its still hypocritical because they will oppose denser housing as well… But if you take that trafic objection seriously, and lean into transit-oriented development, at least the traffic scare tactic is off the table, and when you look at the sustainability arguments, their objections fall apart completely:

Arguing against missing middle housing is arguing FOR traffic, it is arguing FOR cars coming here from out of town, it is arguing FOR climate change, it is arguing FOR wasting of farmland.

To me this is a win-win. We win the housing argument by building the right housing for the right reasons. Ignoring the valid objections to the very real traffic impacts of single family housing is not the right approach.

Very well said Tim … from your very first word until your last.

— the way to “overcome” the objections of anti-development crowd indeed is to LISTEN to them, take their objections seriously, and adrdess their concerns.

— we shouldn’t be building very many single family homes at all because every single family home comes with at least two cars on our roads.

— we shouldn’t be building very many single family homes at all because every single family home produces more expenses for City services than it produces City revenues.

— we shouldn’t be building very many single family homes at all because for the most part the missing middle members working in our community can’t afford homes priced at the level that developers desire

— we shouldn’t be building very many single family homes at all because our history shows that for the most part the residents of those single family homes don’t fill jobs in the City Limits, but rather commute to jobs that are outside the City Limits.

There are so many reasons why single family homes should be out last priority… its easy to forget a few…

I like what Tim is saying, but I’m not seeing a way to get there. Measure J or not, we’re still stuck with a developer-driven model of housing creation. Until developers can be convinced that there’s sufficient ROI to be made by building well-planned high-density projects, we’re not going to get any of them.

“sufficient ROI” really is the question here…

I think that so long as a project clears the developers hurdle rate, they are going to build. Given that we do see higher density projects going up in other areas of town, I think its pretty safe to assume that there is money to be made in multi-family.

Developers’ preference for single-family is either that it is more profitable, or less risky at the measure J ballot box, or easier for some sort of regulatory / legal / permitting reason… or perhaps a combination of the two.

The logic of my approach to a measure J ammendment is that SOME central planning is going to be better than no planning. Until there is a real general plan update, we are stuck with that… But I think the 80/20 rule applies here: So long as the developers get the broad strokes right, the rest can likely be smoothed out in the approvals process, or we can just be happy that we got it 80% right…

Its not ideal, but we are in a situation with no perfect outcomes.

Developers build what they already know how to build, because that reduces their risks. So a developer with a decades long history of building detached single family homes is unlikely to propose a multi-family high density project, unless they have a partner able to provide that experience. Out of town developers who might have the expertise for high density projects don’t want to deal with Measure J and the City’s spanking machine, while local developers who might understand Measure J and local politics, want to build more of what they have done before, single family homes and walk-up apartments.

If we want to move in a new direction, we need to get rid of Measure J and change the City’s negative approach towards development. Otherwise, all we will get is more of the same.

More often than not Mark and I disagree, but this comment of his has a lot of wisdom. It is a basic human nature that people try and do what they know they are good at, so it is no surprise that if the expectations from the City management are as low and as porous as ours are then having a “developer-driven” planning model is the inevitable outcome.

Where Mark and I disagree is in his conclusion that Measure J (which requires a certain level of planning by both the developer and the City management … and most importantly holds the developer and City management accountable for delivering on the committed plan) is a “negative approach.”

The voters have turned down the various projects over the years NOT because of an inbred negative bias, but rather because the City and the developers of those projects failed to produce a plan for the project that would produce a win-win for both the developer and the community.

The projects all added significant traffic to the community (and its neighborhoods) because there aren’t enough $160,000 a year jobs in Davis to make it possible for the residents of the proposed new homes to work here in Davis. The $160,000 figure comes from Alex Achimore’s article yesterday where he commented on a house that costs $700,000 as “affordable without permanent subsidy to families with an income greater than $160,000.” Don Shor has cited similar affordability/household income figures in the past.

If the voters believed their new neighbors would work here in the community, patronizing local businesses, and not heading each day to I-80, they would vote “yes” on the projects rather than “no.” But, as I have said many times before, there is no such holistic planning for Davis. There is no Economic Development Plan that identifies the market segments of the US economy where Davis wants to grow its jobs base … leveraging the core competencies of the community. There is no collaboration with UCD. Instead of capitalizing on the win-win of Healthy Davis Together and coming up with plans for creating additional win-win initiatives together, the City and UCD have fallen back into their historical relationship of ambivalence and/or distrust.

If we are ever going to make progress our community needs to have a plan. Fot the most part developers don’t care about progress. They care about profits.

I agree with Mark that certain developers have certain “wheelhouses” of what they are good at. The failure of the University Commons to transition into mixed use, I think, can be chocked up to that… They basically said “We do strip malls. We dont know how to do mixed use residential and cant find someone who does”. How earnest their search was is anyone’s guess.

That said, I know that for village farms, and perhaps the other properties as well, that the current owners do not intend to be the actual developers, they are planning to sell the entitled land to someone else for construction.

Given that we have a lot of people building higher density housing for the student segment, and we have people building missing middle housing in the Cannery at this very moment. I’m confident that if the property gets entitled as something of higher density, the owners will find a development partner, no problem. It might be a different partner than they intend, but it will still get built.

I have no insider information, but from the news reports at the time, I believe this comment is based on a misconception. It is true that the developer in question was strictly commercial, but when asked by City Staff to propose a mixed-use project, found a partner to work with on the proposal. I suspect that had the project gone forward as originally proposed it would have been completed. The problem of the residential portion not ‘penciling out’ came AFTER the City Council reduced the size of the residential portion prior to approval. It was for this smaller project that the developer was unable to find a viable partner. The problem here was not the developer, it was the City Council demanding changes at the last minute without analysis or consideration of the viability of the altered project.

From my conversations with some in the development team, there were legitimate efforts to find a builder who would do mixed use but the margins were very tight and the compromise needed to get three votes closed off the chances of success.

David, what doesn’t make sense is that there is/was the developer of Davis Live less than a block away, who had just built high rise residential.

I don’t understand your point. There were several factors that were different including the fact that UC was mixed use.

“The voters have turned down the various projects over the years NOT because of an inbred negative bias…”

This is partly correct but I think largely the problem is that people are willing to support housing projects in the abstract but not willing to endure negative impacts that affect their perceived convenience. The only two projects that passed a vote were ones that were seen as not having significant traffic impacts. That’s the lesson I have taken away. I know Matt wants to believe we can have a planning process that addresses that, but I am skeptical that this will ultimately work.

David said … “ This is partly correct but I think largely the problem is that people are willing to support housing projects in the abstract but not willing to endure negative impacts that affect their perceived convenience. ”

David’s comment is only partly correct. He should have said, “ This is partly correct but I think largely the problem is that people are willing to support housing projects in the abstract but not willing to endure UNMITIGATED negative impacts that affect their perceived convenience.”

Like Tim Keller said, “ I think the way to “overcome” the objections of anti-development crowd is to LISTEN to them, take their objections seriously, and address their concerns.”

A few points. First, people choose to live in places for a variety of reasons. I know people who want to live in Davis to be close to jobs at the University. I know others who live here because one person works in Sacramento and the other works in Vallejo and they want to have the kids go to good schools. My point here is all this talk about who is commuting where is meaningless. We have no control over that.

Second the $160,000/year income number isn’t how real estate is usually purchased in Davis. While it is a high bar its not prohibitive for two income families. Also much of the time home purchasers are either move up buyers (although with low interest rates locked in we will likely see less of this for a while) or people with access to intergenerational wealth. For people without equity, access to intergenerational wealth or two incomes the Davis market is often prohibitive. Still there are other ways being proposed that will allow people to get into the Davis market. The Village Farms proposal includes starter home prices in the 500-600 thousand range with down payment assistance through a silent second lien so that young families can get in and start to build equity.

Third, most of the multifamily projects that have been built or are proposed do not allow people to build equity. These, for the most part, have not been projects that include condos, townhomes, or entry level single family houses.

Finally, developers are in it to make money, that is our capitalist system. Like it or not making money is the incentive that drives investment. What is often left out in the constant vilification of developers is that, in the home building industry, a second driver is the opportunity for people who purchase a home to build equity. Davis has made great strides since the days of restrictive deed covenants to accept diversity and inclusion but the more than two decade long aversion to housing construction under Measure J has done little to help people who have limited means to build equity.

Mr. Glick speaks the truth when he states that people have many various reasons for choosing to live in Davis. Those reasons can also change over time because people, their employment and education change over time. The so-called ‘bedroom’ community makes no sense since people have the freedom to reside where they want to. NIMBYs are no different.