In the last election cycle, voters in California sent a message about crime—they voted down Prop. 6, they passed Prop. 36 which increased incarceration for some offenses, and they voted out reform prosecutors in Los Angeles and Alameda County.

They did this out of frustration for what they saw was a rise in crime and decline in public safety—now I would argue that crime data doesn’t support this, but at the same time there is a more fundamental point that the voters and some lawmakers have missed.

Our current criminal legal system makes us less safe because we are failing to provide the basics to those who have been system impacted upon release—housing, jobs, and health care.

On Friday, I interviewed two women about the closure of women’s prisons in California following serious allegations of sexual assault.

They pointed me toward a 2023 report —From Crisis to Care: Ending the Health Harm of Women’s Prisons.

The report finds: “The state of California invests $405 million a year in its women’s prisons. Instead of perpetuating a system that overwhelmingly works against public health, the state has the opportunity to invest that money in health-promoting support systems that people can access in their own communities.”

Quoting at length from the report:

- Safe, stable, and affordable housing: People formerly incarcerated in women’s prisons experience houselessness at 1.4 times the rate of people formerly incarcerated in men’s prisons. Being unhoused can lead to re-incarceration because of the criminalization of houselessness (e.g., sleeping in public places), thus contributing to the vicious cycle of the criminal legal system. Governments should prioritize investments in housing and the supportive programs that people need to stay housed. An evaluation of a supportive housing program for those who had previously cycled in and out of jails in New York City found that, after one year, 91% of those who participated in the program were in permanent housing, compared to 28% of those who did not participate. It is also essential to remove discriminatory practices and policies that prevent people with a record of prior incarceration from accessing housing.

- Increased employment opportunities: The unemployment rate for formerly incarcerated people — around 27% — is nearly 5 times higher than that of the general population, and higher than the overall US unemployment rate at any point in history. Creating employment opportunities for formerly incarcerated people benefits both the employer and the employee. For the employer, research has found that employees with a record of incarceration are less likely to quit and more likely to stay on staff for longer periods. For formerly incarcerated people, employment is a pathway into health via economic security, housing stability, adequate nutrition, and accessible healthcare.

- Affordable health care: Formerly incarcerated cisgender women and TGI people, who often carry extensive histories of emotional, physical, and sexual trauma and violence prior to and during incarceration, have disproportionately high rates of health needs. Investments in community-based, supportive mental healthcare, substance use treatment, and physical healthcare are necessary to keep communities safe and healthy. At the policy level, drug decriminalization and Medicaid expansion for incarcerated people prior to their release from prison will be most effective at improving health outcomes.

-

It is important to note that these three problems are also a factor for men who have been incarcerated. For example, anyone who has been formerly incarcerated is much more likely to become homeless upon release than the general population.

The reason for that is they lack affordable housing, employment opportunities and access to affordable health care.

If we were intentionally designing a system that perpetuated mass incarceration and recidivism—and hence works AGAINST public safety—it is hard to imagine we could do better than the current system.

We make it very difficult—but not impossible—for those who are formerly incarcerated to move on with their lives. They are restricted from certain public housing, they are blocked from many forms of gainful employment, and perhaps least recognized is that they suffer from a number of maladies health wise—both physical and mental health—and lack access to affordable health care.

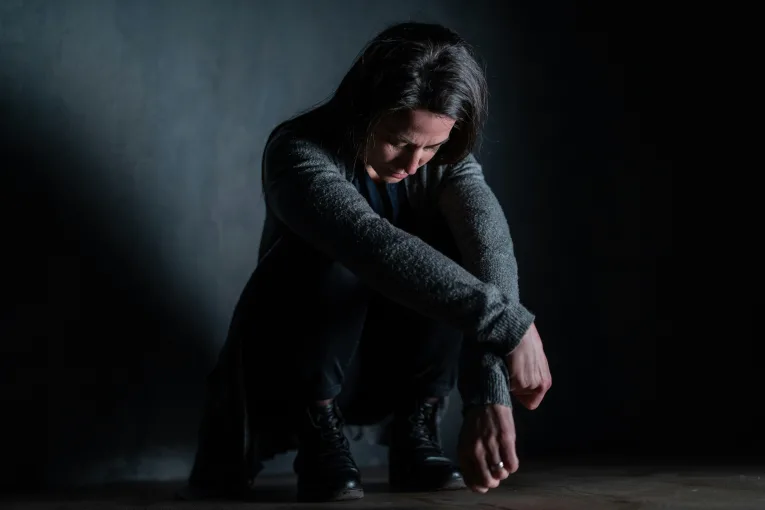

No wonder for many the web of mental illness, substance abuse, and cycles of incarceration are difficult to overcome.

These problems are only magnified for women—who represent the fastest growing body of incarcerated people—because they are relied upon to be caregivers for both children and elderly family members, and have a high underlying incidence of abuse and childhood trauma.

What we as a society need to better recognize, however, is that the linkage between lack of affordable housing which is both safe and stable is in fact a public safety issue. And it is cyclical.

Study after study shows that the vast majority of women who end up incarcerated start out as victims—victims of sexual assault, sexual abuse, and domestic violence.

There is a saying: hurt people hurt people.

This is true of men as well—many of whom started out in life as victims and ended up incarcerated.

But we make it worse: “Alongside the violence of the criminal legal system itself, people incarcerated in women’s prisons also experience and witness high rates of interpersonal physical, emotional, and sexual trauma and violence, which is harmful to both physical and mental health. People incarcerated in women’s prisons face particular violence within the system. In our survey, 47% of respondents experienced sexual and/or gender-based violence while imprisoned.”

We take women who were already the victims of sexual violence and intimate partner violence and subject them to violence at the hands of the very people responsible for their health and safety.

We are not going to make any headway on making our communities safer until we address these issues: it is long past time to start viewing housing and issues of health care and jobs as public safety threats—because they are.

“now I would argue that crime data doesn’t support this”

Have you seen how the FBI adjusted their crime statistics way up from what they initially reported under the Biden admin?

Yup, they lied to us.

https://www.yahoo.com/news/violent-crime-went-not-down-181230239.html?fr=sycsrp_catchall

“When it published the figures last year, the FBI reported that America’s violent crime rate fell by 1.7 per cent, but it has since revised those figures to show it actually increased by 4.9 per cent.”

So it makes you wonder who is behind manipulating the crime statistics to favor Biden’s administration?

It’s what many have been saying all along, they didn’t believe the so-called numbers.

People know what they’ve been seeing and have been experiencing.

The election proved that point.

I think we need to use a different word to describe these folks: they are unhoused… not homeless.

It shows the state of our community– which declines to HOUSE them…