(Or at least it’s supposed to.)

Perhaps the greatest casualty of mid-century modernist thinking was the love affair we fell into with the automobile.

Cars became synonymous with freedom, prosperity, and “the American dream,” and they enabled us to escape the cities and sold us a vision of everyone living in their own little private cottage out in the countryside.

The history of this “great suburban experiment” is equal parts fascinating and disappointing, And we are still feeling its effects today in a variety of ways, but the one consequence we want to talk about today is how we forgot how to build for transit.

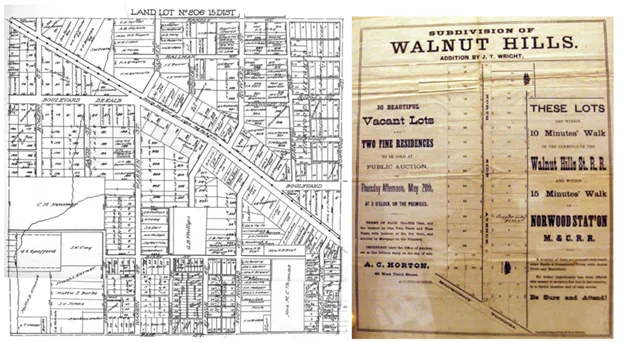

Before the advent of the car, almost every city in the country that had a population above 10,000 people had a streetcar line: a way of moving people faster and more efficiently than walking or carriage. Suburbs were already becoming a thing, but they were “streetcar suburbs”: housing built along the path of a streetcar, trolley or rail line where people could walk from their homes to the transit line, and then take that transit where they needed to go.

The constraint of keeping all of the city’s housing within walking distance of these transit lines forced the cities to remain somewhat compact, and the surrounding countryside fell off into agricultural lands fairly quickly. It also meant that people who were wanting to build housing had first to figure out how to build a transit line to their development, and often, developers did just that.

With the advent of the automobile, however, there was no longer a limit to the city’s horizontal spread, and instead of densifying the neighborhoods around our transit corridors as our population grew, we abandoned the old structures in these older areas, and simply built new housing on undeveloped land on the periphery.

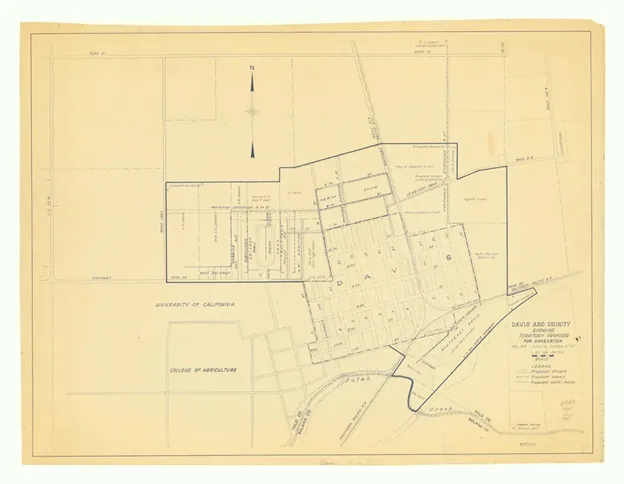

Davis itself also fell victim to this. Whereas our downtown was originally nucleated upon the train station, in the later decades we added significant amounts of single-family housing on all sides, and never once thought about whether we should be organizing the layout of those urban expansions around the need for transit.

The map above shows the initial extent of that first horizontal expansion in the 1920’s. You can see the compact existing limits essentially around downtown, as well as the proposed expansion.

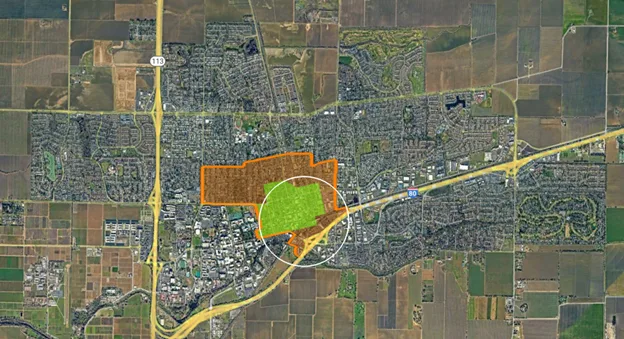

Zooming out, the image below shows those two initial footprints of our city on top of the modern map. (The white circle indicates a half mile radius centered on the train station downtown.)

Davisites sometimes talk about our city being “small” and “bike friendly,” but in reality, we are without a doubt already a sprawling and almost entirely car-dependent city, and have been since the 1960s.

What is worse is that with so much land committed to very low-density housing, it is almost impossible to retrofit such a suburban landscape to one that is more sustainable. Once property lines and streets are laid out and built, and small lots sold to different owners, it’s very hard to change usage types without breaking out the bulldozers in highly traumatic ways. So in most cases, the damage is done.

Which brings us to the crux of this challenge:

- We have already discussed in a previous article the variety of reasons why it would be irresponsible for us to perpetuate this unsustainable pattern of low-density sprawl by approving any more car-centric developments on our periphery;

- We nevertheless have a variety of other reasons for us to want to grow our housing supply dramatically: Environmentally, economically, socially and morally;

- While infill opportunities are ideal, there aren’t nearly enough of them to move the needle; not for our next-cycle RHNA obligations, and not if we want to repatriate even a fraction of 23,000 inbound service workers / teachers / university staff that commute in every day;

- Doing “nothing” and just letting the housing growth occur in adjacent cities doesn’t mean there are no traffic impacts; it just makes the commutes longer for those who work in town but can’t afford to live here. And that also increases greenhouse gasses that we all are affected by.

- Conversely, adding to the local inventory of detached single-family houses will DEFINITELY make traffic worse in Davis. That’s because any detached house here will sell for at least $700,000, and our city is not growing enough jobs that pay the salaries necessary to afford such prices; so those new residents will likely be working out of town and adding to the existing rush hour commute traffic of 18,000 outbound workers as well.

Bottom line, we need to find some other way of developing on the periphery that isn’t just more car-dependent sprawl. We need to build in a more sustainable way and try to find a way to REDUCE traffic in the long run.

Let’s talk transit-oriented development

Here is where we get to the good news, because such a sustainable option IS possible here in Davis for developing better housing on our periphery. All that is required is getting back to the “streetcar suburb” model that existed before the advent of the automobile.

This is not a new or untested concept. And the basic concepts behind it are so universal among the various urban planning experts that they end up coining their own terms to talk about basically the same things:

- “Walkable cities”

- “15 minute cities”

- “Transit Oriented Development”

- The “LEED-ND” Rubric

These are all merely re-packaging the same handful of successful planning concepts, and they all quite directly involve rejecting the assumption that “everyone will drive in a private automobile everywhere for everything”

The universal starting point in all of these philosophies is to think of transit systems FIRST: Think of ways that you can allow people to navigate your development without resorting to a personal automobile.

That means designing around transit lines primarily and then putting a heavy emphasis on creating VERY safe, and well connected bike lanes that are not just stripes of paint on otherwise automotive corridors.

As urban planners have figured out how to do this well, a number of best practices have emerged:

- Transit occurs along corridors, in lines that need to be relatively direct in taking people to important employment and shopping destinations.

- People tend to choose transit over driving, especially when doing so is FASTER than car travel. So the transit service needs priority: dedicated transit right-of-ways and signal priority when transit shares streets with cars.

- Transit is more cost effective when there is a larger ridership base of people within ¼ mile of stops and where the transit goes to within ¼ mile of the destination. So planning for moderately dense and compact “walkable” neighborhoods and commercial districts all along the transit lines is also important.

What emerges from this set of needs is the concept of Transit-Oriented-Development (TOD), which ends up looking like a plan for a transit line, including proposed stops along that line, and plans for what kinds of housing, jobs, and services can be located at those stops. It is an integrated, high-level plan for a city based on transit service as well as pedestrian and cycling access.

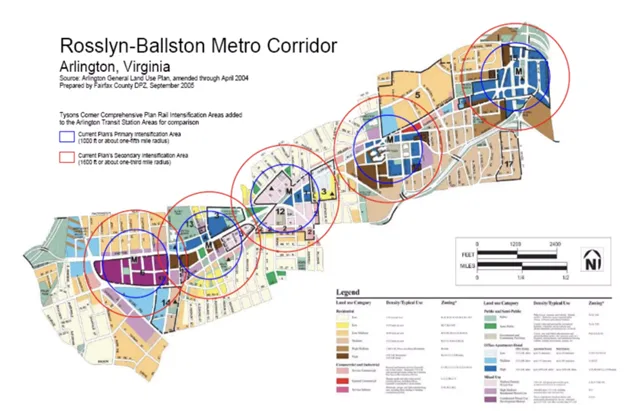

There are many examples of where this kind of alternative thinking has paid dividends, and the plans all take roughly the same approach: it is a “string of pearls” sort of city planning where the line is established first, and then stops are planned, and then neighborhoods are designed around those transit stops.

Here is an example of “streetcar suburb” planning outside of Washington DC… ( only here, the streetcar is the DC Metro)

There are a number of projects like this around the world where a transit-oriented approach has been used to create very attractive, even popular, new neighborhoods on the outskirts of larger cities without reliance on car infrastructure. And several cities in the United States have recently followed suit. Here’s an example from outside Portland, Oregon:

Transit from Scratch

For many reasons, Europe has lots of great examples of transit-oriented towns and cities, and, while we are not proposing to copy them exactly, there are models and principles we can learn from.

One great role model for us should be Freiburg, Germany, which is also a university town that has a significant amount of bikes. There is a great video about it HERE, and if you watch that, you will get a much better idea of how comfortable, attractive, and convenient a city can be when transit comes first, bikes second, and cars last.

In Freiburg, they make it simple: They do not permit ANY construction of housing that is not within walking distance of a transit line. But Freiburg had many local streetcars before the automobile arrived on the scene, and though the city was destroyed in WW2, they chose to keep their public transit rather than re-build for the automobile.

The United States, in fact had, many suburbs served by streetcars in the first half of the 20th century, but a concerted effort by the oil companies and the rising popularity of the automobile caused this form of transit to largely be removed (tracks pulled up) in the 1940’s. You can watch Disney’s “Who Framed Roger Rabbit” for a humorous take and/or read From the Archives: Did Auto, Oil Conspiracy Put the Brakes on Trolleys? – Los Angeles Times for a more complete account of this chain of events.

Most of the City of Davis, on the other hand, was developed into car dependency after the rise of the automobile, and the only “transit” system we have (Unitrans) is largely focused on moving students to campus. It has never been intended to be a generalist service to the citizenry of Davis.

Trying to lay out a more typical transit service on top of a city made for the automobile is normally pretty difficult because the streets are rarely designed for it. But at the moment, we have a unique opportunity: there is a string of properties bordering an existing primary automotive corridor that have been submitting plans for new development: Village Farms, Shriners, On the Mace Curve, and the property known as the Davis Innovation Sustainability Campus (DISC). Taken together, and if developed with sufficiently dense housing clustered near Covell, these projects could form the backbone of a new transit corridor.

Above is a transit line concept that was first proposed in the Vanguard almost two years ago. It crosses all of the properties (highlighted) that are currently or recently under consideration for development. It would also provide incentives and direction for the properties in between who likely are considering their options for the long run.

On one end it connects these new neighborhoods to downtown and ultimately runs onto campus. The line can connect via the already moderately dense F, J or L street corridors and our Amtrak station along the way..

On the other end, it connects to the previously proposed innovation campus (DiSC) site, which is still likely the most sensible spot for additional commercial development to serve our local economy, and could serve as a “business district” for our city.

Note as well that this line would make AMTRAK a much more viable mode of extended transit for Davisites, since those within walking distance of this line do not have to drive their car to the train, and inbound travelers would be able to easily access campus and much more of our city.

What about bikes and E-mobility?

We have had to edit out a discussion of bikes from this article as it simply got too long.

We believe that E-Bikes have definitely raised the potential for Davis to transition from being a merely “bike friendly” to more of a “bike centric” city, but we will discuss planning concepts for bike infrastructure as part of our exploration of alternative designs for both Village Farms and the Shriner’s sites, or as a standalone article if people express interest.

The primary point of this particular article is how to think differently if we laid out our city with transit in mind and about the particular opportunity we have at the moment to realign our concept of what the northeast corner of our city might look like if we did that.

Is high-frequency (good) transit possible in Davis?

For transit services to truly compete with automobiles for ridership, the service not only needs to connect housing density to commercial and employment destinations, it needs to be quite frequent: one pickup (by bus or trolley or streetcar or whatever we end up picking) every 15 minutes at the very least.

Is such a service economical in “small town” Davis?

There are multiple answers to that question.

- Yes, it is economical. We picked the target density of 20 units per acre in our previous article partially because it is a threshold housing density that makes trolley / streetcar systems like this cost efficient. More people within walking distance of the transit line means more people that line can efficiently collect which means more ridership.

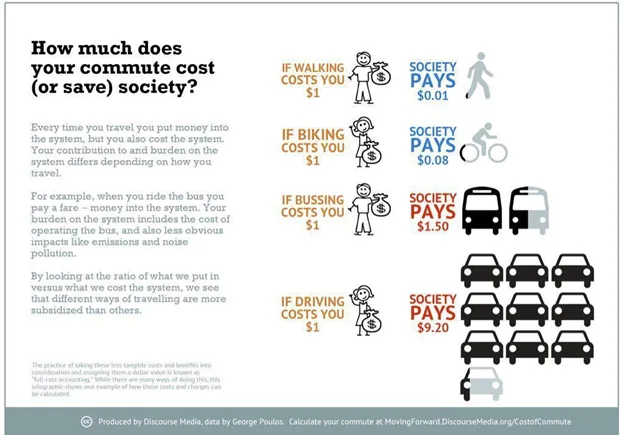

Wondering if the transit service pays for itself ignores the fact that the alternative (private car transit) is entirely subsidized, and to a much greater extent than transit could ever be.

We have become quite entitled societally to expect the government to provide us with well-paved roads leading everywhere we want to go, plus we expect free parking in lots and curbside that take up 25% of our urban land. We see that as our right. Do we ever question whether that expense is justified?

The following infographic makes this point pretty well:

If we really care about reducing VMTs and mitigating traffic, we should be willing to divert highly inefficient investments in car infrastructure into investments in bike infrastructure and transit.

Neighborhood Centers

The last high-level concept to discuss as we are talking about transit-oriented-planning is how the concepts of the “15 minute city” and “walkability” overlap with the practice of transit-oriented development.

Think for a second, about your current grocery shopping experience.

Most Davisites drive their cars to a shopping center that has a large parking lot out in front of it, in the “strip mall” configuration. Consider this picture of Oak Tree Plaza taken from Cowell Boulevard:

If a transit line dropped you here, you would still need to walk a hundred yards through a parking lot to get to the stores.

Contrast that shopping center with the Davis Commons, which is part of the much more walkable fabric of our downtown. Yes, there is a parking lot here, but it is behind the stores, creating a bike and pedestrian-friendly place up front where you can frequently see people eating outside and children playing.

This is a minor change simply in terms of “where do we put the parking lot” but it makes a large difference in terms of how well we cater to people walking, or taking transit. So transit oriented design means taking the design of the neighborhoods around the transit stations into account as well. It is not enough to just drop people off into an otherwise car-centric landscape.

Best practices for TOD include the development of “neighborhood centers” at many of the stations along that transit line. If each stop is a bulls-eye along the transit line, as you saw in the Rosslyn-Ballston example above, you will want the highest density uses in the center of that bullseye tapering off to lower-density uses further away from the stop.

This creates a “mini-downtown” kind of feel: a nucleus for the local neighborhood and a place to shop and to gather socially. An example of such a neighborhood center is visible in the Orenco Station picture above and there are a variety of other successful developments also using this model.

Not every transit stop needs such a neighborhood center, but they should at least be distributed along the line so that no point on the line is very far away from these kinds of everyday / community spaces.

Conclusion:

The peripheral properties currently considered for development in the Northeast corner of our city represent a precious opportunity: An opportunity to reject the failed pattern of car- centric suburban sprawl, and embrace a much more sustainable model of transit-oriented development.

It is rare for an established city to have an opportunity like this, and we will not likely have it again. If we want to provide the housing we need AND see our traffic and parking situation improve (not worsen), this is really the only way to do it.

The development teams for both of the peripheral projects have a very specific job: They want to win a Measure J vote and provide whatever housing they can. But that vote creates an incentive for them to not want to rock the boat—to not propose anything that the community might see as controversial. So they are sticking to just producing “more of the same” suburban sprawl… the same kind of housing that urban planners already know is a mistake.

On the city side, because of Measure J/R/D and the lack of a general plan update, we have largely abandoned any long-term civic master-planning function, and so the ideas proposed by the developers are going to be the ONLY ones that see the light of day.

This is probably the worst possible way to plan a city, and this is why we in the community need to be stepping up to ask for something better. It isn’t going to come any other way.

We have a real and rare opportunity to implement a vastly superior urban planning concept and we have time to get it done. But we will lose that opportunity if we allow any of these projects to be planned without putting transit first.

The Davis Planning Group

Alex Achimore

David Thompson

Anthony Palmere

Richard McCann

Tim Keller

Count me in.

I haven’t read this yet, but I fully agree with the title — and this concept fully is NOT happening. We, as Davis, are already the Coyote in Roadrunner: off the cliff, suspended in mid-air, and about to fall.

So eager to build baby build, that we are willing to build wrong.

The key is the map shown — basic route for a transit and bicycle corridor is correct in it’s general coverage. There are some details that should be refined to improve it, but it is very close to the route concept I would draw as a professional transit planner. I have spoke to TK about some design improvements, but the basic route concept is correct.

The major key is land use design around the transit route, as the KEY to project design. Design very high density around the transit route, medium density further away, and low density such as single family houses furthest away. This need not be gr

But land use planning around a transit route is MOOT since there is no key transit route that developers are being asked to build around. So we get a series of auto-centric blobs with an entrance on Covell/Mace.

And the Coyote falls . . .

As I’m sure you would be the first to point out: drawing lines on a map does not create a transit system. There are going to be LOTS of people at the table, and there are lots of ways we can design the service, and the service itself is likely to evolve over decades and there are a lot of detailed small decisions that are going to be important.

At this point in time is to point at the horizon and start marching in the same direction, stating that this is the way we want to go.

How we get from this as a concept to the city embracing it formally and developers designing their projects around it is really the challenge. I think that perhaps the immediate first step is that all of us need to submit comments to the VF Draft EIR process asking for a Transit-oriented scenario. (?)

“At this point in time is to point at the horizon and start marching in the same direction, stating that this is the way we want to go.”

Good luck with that. I have no idea where you think new residents would be commuting to in the first place. Or where you think they’d be coming from, if they built a commercial development on the outskirts of town (as you advocate).

Regarding the “need” for housing, young people aren’t even having kids at anywhere near “replacement levels”. 1.64 kids per woman these days (nationwide), well-below the 2.1 level needed for replacement of the existing population. This is an astonishing change.

All that’s occurring right now is shuffling around the passengers on the deck of the Titanic, so to speak. Even Elon is worried, perhaps because he needs some expendables to send to Mars.

Though even I sort of appreciate that you don’t want traditional sprawl.

There are 29,000 workers commuting into Davis & UCD now, and 18,000 commuting out. We need to build housing for that first group to reduce the VMT in our community. Many of those will be able to commute by transit and bike to workplaces in town. That’s who we’re building housing for; we want to get them off Road 102 from Woodland.

“That’s who we’re building housing for…”

Frankly, Richard, this is your basic problem. You are trying to produce housing for a specific subset of people. That sort of top down, command and control approach is historically what has caused most of the problems in Davis. WE NEED MORE HOUSING. Stop trying to dictate who will use it.

I don’t know what good that would do, re: “all of us need to submit comments to the VF Draft EIR process asking for a Transit-oriented scenario.” You can’t have decent transit without a decent ROUTE. Once something has been built without that, it means any future planning has to go AROUND, which degrades transit for all using it, forever. There has to be a City plan for all developments on the N and NE side to plug into. Therefore, convincing the Council is the only solution, and that seems like pushing a boulder up a hill and having it fall on you.

I think I agree that convincing the council is necesssary, but I dont think thats impossible.

Planning for transit is really the only way to NOT be planning for the car right? I think most people understand the basic truth of that.

The only thing that I worry about is potential backlash from car drivers who might worry about spending 10 more seconds at a traffic light because a bus has signal priority, or residents who don’t want to yield on-street parking for the sake of better bike lanes and transit.

I keep thinking of the protests in Amsterdam that happened when that city made these kinds of changes. There were fistfights in the streets between activists protesting the fact that cars were killing kids, and entitled drivers wanting to make it past the protest barricade they had erected. The planning commission there had to hire bodyguards because merchants were making death-threats, worried that when you close off car traffic, nobody would walk to their stores… only to of course find out that foot traffic increased once they removed the cars…

There is going to be SOME level of that resistance from auto-centric davisites,.. Thats the only thing that I’m worried about.. the council worrying about THOSE voters, and not having the political courage to make changes that they dont understand.

From article: “Doing “nothing” and just letting the housing growth occur in adjacent cities doesn’t mean there are no traffic impacts; it just makes the commutes longer for those who work in town but can’t afford to live here. And that also increases greenhouse gasses that we all are affected by.”

First of all, “doing nothing” is not what’s been occurring in Davis. But as I mentioned yesterday, Davis has no control over what occurs in “adjacent” (nearby) cities. Start with that.

But perhaps more importantly, there aren’t a lot of new jobs being created in the city OR on campus. As such, the commute to (or through) Davis is not likely to increase much. Other than from people traveling through Davis to another destination (e.g., to avoid gridlock on I-80). Davis is “in the way” of those travelers, and is not viewed as the center of the universe.

And again, all of this seems to ignore the fact that these developments will result in an OUTBOUND migration (e.g., to Sacramento). Especially since they’re proposed for the east side of town.

Regarding transit, have you seen what’s happening regarding lack of demand for it in the Bay Area (e.g., due to telecommuting)?

If dense housing is built on the periphery of Davis, you already know “who” is going to occupy it – students (and some who commute to Sacramento). Is that the goal – to house students on the periphery of Davis in dense developments?

I have no idea what the goal actually is, other than to develop farmland.

Welcome back Ron.

They key fact here is our 23,000 inbound commuters. We are in a DEFICIT for housing to a much larger extent than any of these projects have even a chance of making up.

Our university and our economy have grown and we havent. The “traffic” is happening whether we build housing here or not, and the VMTs are much worse.

So if we care about the environment, or our economy, or traffic, we need to be building housing exactly for this population of inbound commuters. Nobody else is a priority.

Thank you, Tim.

Regarding the inbound commuters (to UCD, not Davis), David today noted (in his other article) the “huge numbers” of outbound commuters.

How about if these people just switch houses? Or, switch jobs? 😉

And by the way, does everyone in a given household commute to the same location/city?

Also – where are you claiming that workers at DISC, for example, would live if that ever resurfaces (as you’d prefer)?

Missed this quote, the first time:

“Our university and our economy have grown and we havent.”

UCD doesn’t “belong” to the city, but regardless – it’s the STUDENT population which has largely grown. I don’t believe they’re adding significant numbers of staff members at this point.

And the local (Davis) economy isn’t growing.

Ron

Oops, wrong answer. UCD has never had and never will have an obligation to build housing for its staff (putting any commentary about student housing.) And UCD is quite literally across the street from us, and most of that VMT passes through Davis in some form. And UCD brings $1 billion in annual economic activity to Davis and Yolo County. So its our biggest issue and biggest single economic driver. The rest of us aren’t so naive as to believe that we can ignore UCD in planning for housing and transportation needs. Everyone who lives in Davis realizes the importance of UCD to the community and our role in maintaining that presence.

El Macero was the epitome of car-centered development back in the early 1970s and, unsurprisingly, the center of opposition to attempts to undo or mitigate dependence on the single vehicle transportation concept as we witnessed with the Mace Blvd. reimagining and then, unimagining. I support your transit line concept to the point of accepting, gasp, increased taxes to help pay for it.

It shouldn’t take more taxes. The concept only needs to be the establishment of a route that goes through all the proposed projects. The Planning Group and I agree on the basic concept for this — very closely. So who needs consultants? The issue is going to be to get the City Council to realize how important this is, stop, incorporate this into all proposed projects even if this means #gasp# re-design, and *then* move forward.

“The issue is going to be to get the City Council to realize how important this is, stop, incorporate this into all proposed projects even if this means #gasp# re-design, and *then* move forward.”

Would that be the same City Council that listened to staff tell them that the cost of building an affordable unit is $608k and then voted 4-1 to set the affordable in-lieu fee at $250k?

almost $369k, but instead of studies to estimate what various numbers would give, they just batted around feel-good numbers and went for one. I’m surprised the didn’t choose an in-lieu fee of $69,420.

I generally agree with most of this – including Alan Miller’s comments, but:

* The examples you show consist of extremely robust transit services with very short headways, or services that connects to robust regional rail, or both. But the newly released State Rail Plan only shows half hour headways for train station in Davis

* Related, many European examples of TOD would have a main line connected to a branch line to the next town, in our case, Woodland. The rail line could be made available and Woodland could be redeveloped to support it.

* If DISC 3.0 is built, why would people commuting from the east want to travel all the way downtown only to backtrack to the edge of the city? This is partly a psychological thing: many European towns have peripheral stations on main lines but which are only served by some trains. The area around Mace is perfect for this, but doesn’t seem to be considered in the state rail plan (Just like activating the train station in Dixon, and that City just got a huge grant for a needed overcrossing of the rail line that doesn’t do anything for the train station).

* There are still automobile and extraction industry interests in town working for car dependency.

* We need further discussion on people with cars who choose to take transit. And all the regional trips by car that will be made by people who live in these places, driving past the new road death micro-cemeteries on 102 that will become financially viable if all these projects are built.

* Cycling and Transit support each other, so it’s important that he further discussion from the Planning group focuses on connectivity in the new proposed developments and from those to the rest of the city.

* Note that the city is about to apply for a half million dollar citywide transportation planning grant for a process that will not be over until 2028, well after the street plans for these projects are laid down. I believe that that’s intentional: to create a mechanism that lets the developers decide things in the interim. And it doesn’t directly involve UC Davis, so it’s a conceptual clusterfrack to create a new template for only part of the reality of a connected Transportation ecosystem involving the city and campus.

* The examples you show consist of extremely robust transit services with very short headways, or services that connects to robust regional rail, or both. But the newly released State Rail Plan only shows half hour headways for train station in Davis

1/2-hour headways is more than enough and will require billions in upgrades to the infrastructure. 1-hour headways are within reach with some additional equipment, a couple of modest infrastructure upgrades and negotiations with UPRR. I’m not sure what you mean by “the examples you show” as in what examples, who is “you” ?

* Related, many European examples of TOD would have a main line connected to a branch line to the next town, in our case, Woodland. The rail line could be made available and Woodland could be redeveloped to support it.

It’s all about potential demand and operations. If you model a station on a regional system so close to another station, the capture zones overlap greatly, i.e. it will benefit a small segment of population, but the additional running time (which discourages use by those already using the service) and fuel to start and stop are not worth the small margin of increase. CCJPA also has a station policy that does not allow stations spaced so closely together. It seems like it makes sense from a Davis perspective, but as a regional service it does not.

* If DISC 3.0 is built, why would people commuting from the east want to travel all the way downtown only to backtrack to the edge of the city? This is partly a psychological thing: many European towns have peripheral stations on main lines but which are only served by some trains. The area around Mace is perfect for this, but doesn’t seem to be considered in the state rail plan (Just like activating the train station in Dixon, and that City just got a huge grant for a needed overcrossing of the rail line that doesn’t do anything for the train station).

They would not make sense to those people to backtrack, and in very large cities this very concept is of value. For example, I implemented the Old Town Station in San Diego about ten years ago as part of a schedule restructuring, and it has been a banging success, because it keeps people from having to backtrack into the core to catch the train. However, the short-distance, tiny relative population, and lack of obstacles to reach the station don’t justify the expense. While, again, it makes sense from a Davis perspective, new stations cost around $50 million give or take a few tens of millions, and the very slight increase in ridership cannot justify state investment relative to 100’s of other projects that would give much better value for money and ridership increases. In other words, money is limited, and agencies have to justify their projects. In a few 100 years when there are four mainline tracks, a more local service is possible that stops in West Sac, Mace, Dixon, etc. But that is not even on the horizon for our lifetimes nor for many generations. It’s important to invest and build for what is best for the state, not pine for a local want.

* There are still automobile and extraction industry interests in town working for car dependency.

I have no comment or evidence nor have any idea.

* We need further discussion on people with cars who choose to take transit. And all the regional trips by car that will be made by people who live in these places, driving past the new road death micro-cemeteries on 102 that will become financially viable if all these projects are built.

I have no idea how to comment on a comment like that so front-loaded with dramatic commentary.

* Cycling and Transit support each other, so it’s important that he further discussion from the Planning group focuses on connectivity in the new proposed developments and from those to the rest of the city.

Absolutely. But don’t forget, the Planning Group is self-declared. It doesn’t even have the authority of City committee. The only way to action is to convince the Council.

* Note that the city is about to apply for a half million dollar citywide transportation planning grant for a process that will not be over until 2028, well after the street plans for these projects are laid down. I believe that that’s intentional: to create a mechanism that lets the developers decide things in the interim. And it doesn’t directly involve UC Davis, so it’s a conceptual clusterfrack to create a new template for only part of the reality of a connected Transportation ecosystem involving the city and campus.

I doubt it’s intentional. Very few people understand transit planning or it’s importance — important often to their very goals. More the fail is the build-baby-build, cart-before-horse philosophy that won’t allow them to slow down and make the necessary hard decision to ask for a reboot of all the projects to conform to a transit/last-mile-vehicle corridor. I am not minimizing how difficult this would be, but the consequences of not doing it will hurt the City and its goals — forever.

Oh, I didn’t catch the Woodland comment. Again, far too small a population to attract rare infrastructure dollars for a rail line of only 12 miles. While a nice fantasy, this would be a catastrophic waste of transportation dollars.

Following up on Alan’s comment, why does it have to be expensive rail? We have the ability to build much lower cost dedicated roads for electric buses if we believe that there is enough traffic volume. It’s not a case of “rail is the answer, now what was the question?” Think more innovatively.

And Alan, thanks for both all of the planning insights and the work you’ve done elsewhere. I’ve used the Old Town station!