By Ramneet Singh and Lauren Smith

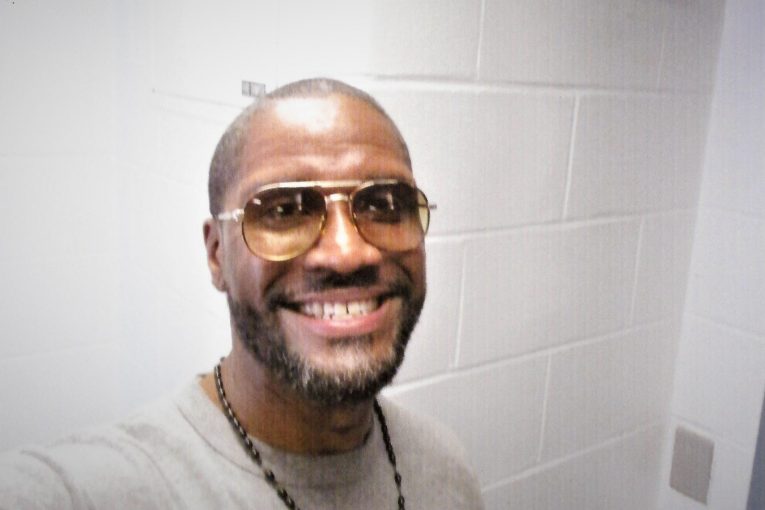

TERRE HAUTE, IN – At 9:27 p.m., Thursday, Dec. 10, Brandon Bernard was executed by lethal injection in a federal prison facility in Indiana.

After the first federal execution in the Presidential transition period in more than a century, the death of Bernard highlights the necessity for legal accountability.

Some Justices of the U.S. Supreme Court agreed, and wanted to stay the sentence Thursday. But not enough.

Bernard, 18 at the time, was convicted in 1999 for his part in a double murder committed the previous year in Fort Hood, Texas. In 20 years on death row, Bernard and his legal team accumulated evidence that could have altered the outcome of his trial—his legal team found “the government had withheld information during his trial that may have helped his case…”

The Bernard case garnered the attention of the American public, with the mass sharing of information on social media platforms Twitter, Instagram, and more.

In the last-second appeal to the Supreme Court to stay his execution, Justices Stephen Breyer, Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor would have granted a stay, with the latter writing the dissenting opinion.

In her opinion, Sotomayor found Bernard’s allegations of withheld evidence “troubling” and would have granted him an opportunity to prove his case. Foremost, Sotomayor referenced the inadequacies  of the prosecution’s claim of “Bernard’s future dangerousness” in light of a witness testimony by Sergeant Sandra Hunt in a related case.

of the prosecution’s claim of “Bernard’s future dangerousness” in light of a witness testimony by Sergeant Sandra Hunt in a related case.

Hunt provided that the gang that Bernard was tied to was hierarchical and that he was “…at the very bottom.” Hunt’s testimony clarified that the prosecution was aware of this fact.

Bernard and his legal team established the claim on two grounds: the government violated its obligation to reveal evidence pertinent to the ruling and the false testimony of his role in the gang.

According to the Fifth Circuit Court ruling, because Bernard had previously petitioned his death sentence, his following petitions were subject to strict guidelines that require incarcerated people to produce new evidence that demonstrates that it is unlikely that the defendant would have been found guilty had this evidence been presented earlier.

However, Justice Sotomayor stated that the Fifth Circuit Court “got it wrong” because the “illogical rule” conflicts with precedent established in Panetti v. Quarterman. This case established that regulations on successive petitions do not apply to a claim that was not ready when the defendant filed his first petition.

In Justice Sotomayor’s words, “How exactly was Bernard supposed to have raised a Brady claim more than a decade ago when he brought his first habeas petition, given that he was unaware of the evidence the Government concealed from him?”

Justice Sotomayor further wrote that strict rules like this reward both the government and prosecutors “for keeping exculpatory information secret until after an inmate’s first habeas petition has been resolved.”

In doing so, prosecutors “avoid accountability” and “run out the clock” as long as they can prove that the evidence they failed to share with the defense is not sufficient enough to demonstrate that the defendant is innocent, the Justice noted.

Justice Sotomayor concluded that if prosecutors had not violated Bernard’s Brady and Napue rights, he “would have been spared a death sentence” and that he “should not be executed before his claims have been tested under the correct standard. Nor should others like him find themselves procedurally barred by similarly perverse and illogical rules.”

Ramneet Singh is a third-year student at the University of California, Davis. He is a Political Science major and is pursuing a History minor. He is

Ramneet Singh is a third-year student at the University of California, Davis. He is a Political Science major and is pursuing a History minor. He is  from Livingston California.

from Livingston California.

Lauren Smith is a fourth year student at UC Davis, double majoring in Political Science and Psychology. She is from San Diego, California.

To sign up for our new newsletter – Everyday Injustice – https://tinyurl.com/yyultcf9

Support our work – to become a sustaining at $5 – $10- $25 per month hit the link: