Exonerated Inmates Receive No Services and Often Face Health, Mental, Educational, and Financial Hardships Upon Release

It was billed as one of the largest gatherings of exonerated inmates, mobilized by Exonerated Nation to meet with legislators in hopes of getting new laws to provide benefits and services to exonerated inmates upon their release, after spending at times decades being wrongly incarcerated.

Unlike parolees who have access to $200 “gate money” upon release and numerous services, the exonerated inmates, innocent of any crime, are sent “home” with nothing and get no help transitioning from prison to real life.

They arrive home to find family gone, friends gone, no support system, no job skills – and facing the prospect of homelessness, the specter of PTSD, and a system that is indifferent to their suffering.

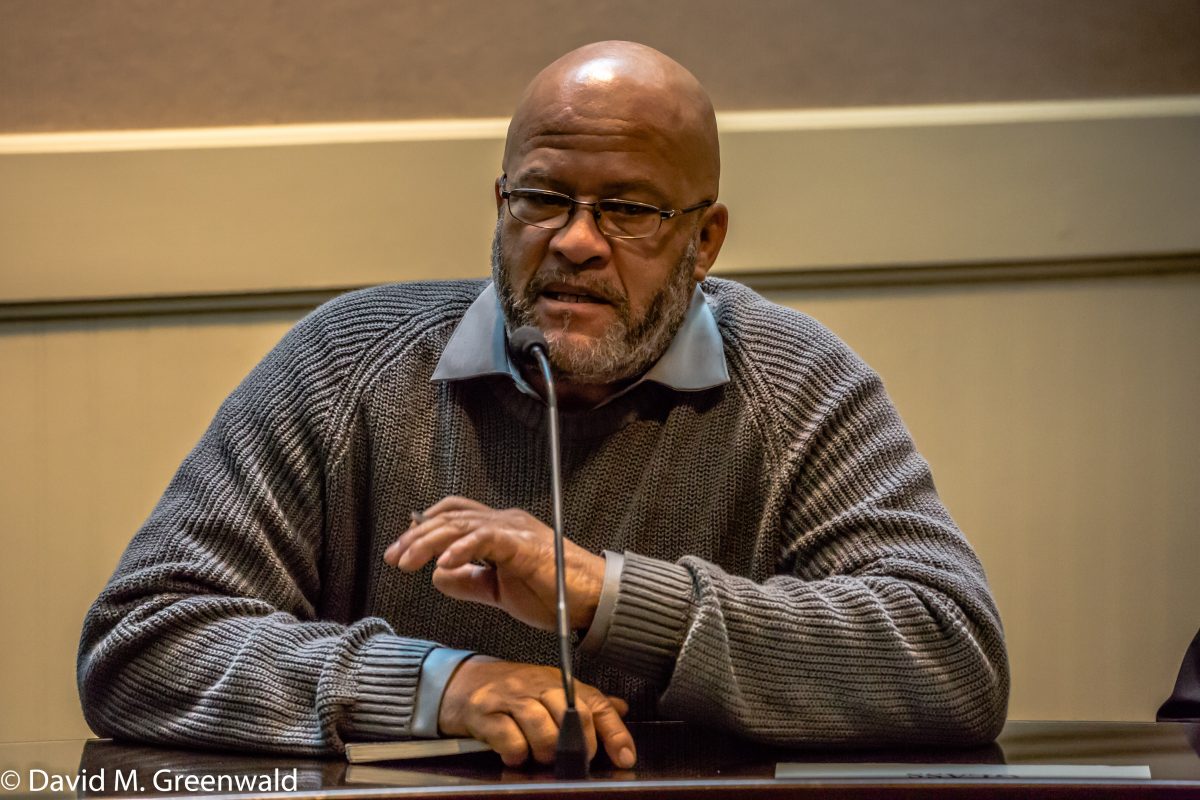

For Obie Anthony, he was wrongly convicted in 1995. He explained, “I spent 17 years in prison for that crime which I didn’t commit.” He originally faced the death penalty, then ended up with LWOP for a murder and three attempted murders

He would finally be exonerated in 2011 with the help of the Northern California Innocence Project (NCIP).

Now he explained, “I am actively involved in assisting other inmates who suffer the same plight as me and I started Exonerated Nation.”

Among the things that went wrong leading to his conviction: faulty identification, faulty testimony, police misconduct, and prosecutorial misconduct regarding suppression of exculpatory evidence, Brady violations.

According to published accounts: “During the hearing Anthony’s lawyers demonstrated the prosecution’s key witness had lied repeatedly at trial and that the prosecution knew of his lies but failed to correct them for the jury. They also presented evidence that the prosecution suppressed evidence that impeached its witnesses, that Anthony is actually innocent, and that Anthony’s defense attorney at trial failed to investigate and present information that suggested Jones was the actual killer.”

An investigation, Mr. Anthony stated, “showed that their star witness had made the whole story up.” He had “made other identifications that didn’t fit me.”

As the moderator explained on Wednesday: “One of the things that the folks here at Exonerated Nation have been sharing and (have) talked about, both the challenges on the front end and how they end up in

prison when they shouldn’t be, for a crime that they did not commit. All the work that it takes to get them out, it’s not an easy process to get released. It takes them years and years and years… Then we’re also talking about what happens (when they are released).”

Obie Anthony was just 19 when he ended up at the penitentiary. “I didn’t walk out of the penitentiary until 2011, I was 37 years old.

“The good part of when I walked out of the door, I was free. I had the power of freedom. That was the good part,” he said.

“When I got out, there was no programs for me to go to,” he said. He had health issues, problems with his teeth, and a misdiagnosis for a hernia that turned out to not be a hernia. “I didn’t have a place to get myself checked out because I knew how bad I was doing. Had it not been for my wife… I had no place to go.”

His mother had passed away while in prison, and he had no support system. He relied on the folks at the Innocence Project for basic clothing and things like toothpaste.

“I walked out of the door with somebody else’s clothes on because they didn’t have mine,” he said. “That was the bad part for me, I came home to absolutely zero. I had no education.”

He taught himself things while in prison, but that was based on books he found at the prison library and he didn’t have any background on technology. He said he had trouble taking photos with his phone and he’s only now, six years after his exoneration, figured out how to use email and put messages in folders.

Parolees are provided a minimal level, but some levels of services upon release. But for exonerees, there is nothing in the statutes that provides similar services.

“There was no services,” Mr. Anthony said. “All of us are suffering from PTSD. None of are getting those really good night sleeps… So we suffering.

“I refuse to be home and have the power of freedom and not come here and say something,” he said. “I refuse to stop working now.

“There was nothing there,” he said. “There was no transitional services. There was no education. There was no help.”

Maurice Caldwell was the keynote speaker back at the 2011 Vanguard event on Wrongful Convictions. He was incarcerated for 21 years.

“I was wrongly convicted of a drug-related murder in the housing project where I grew up – a drug infested housing project,” he explained.

Mr. Caldwell was convicted in 1991 when he was 22 years old. He would not be released until 2011 when he was age 42.

He was released and had no support. “My immediate family, every last one of them, passed away,” he said.

He said that in about 2003 he finally got in touch with the Innocence Project. Paige Kaneb of the Innocence Project reinvestigated the case as the homicide investigators didn’t do.

“People are always asking me, what was it like to be released. When I was first released the freedom of being – I had a Tony the Tiger attitude – I said I would never want nobody bad to walk up to me and ask me how I’m doing and I’m going to tell them, great.

“When I got out, I had no resources at all,” he said. “I didn’t have nobody. I didn’t have no family – I had one sister. She was there. She was my only resource.

“When they opened the door, it was nothing,” he said. “They just threw me out like I was in the drunk tank.” He pointed out, “I wasn’t just an exoneree, I was a victim of the system.”

Today he said, “I’m homeless. I’m semi-homeless. If it wasn’t for Exonerated Nation, I would be homeless.

“I always wanted kids, I have no family,” he said. “When I got home people judged me, why would you want a family, you don’t even have a job.

“People don’t understand what an exoneree goes through,” he said.

William Richards, unlike many of the others, was quite a bit older when he was convicted of killing his wife. San Diego County put him away for 23 years for murdering his wife.

It took four trials to convict him based on documented perjury from the police, solid evidence that they destroyed exculpatory evidence.

In 1993 he was 43 years old, an engineer, had friends, a family, a full life. When he got out of prison in 2016, he was 67 years old and was diagnosed with advanced cancer. His family had died and many of his close friends died.

“When I came out the door, I came out with nothing,” he said. “When a parolee is convicted of a crime, he gets services. When an exoneree comes out and they kick you out the door, they fill your bed, and you‘re gone. They want to forget you because you’re an embarrassment.

“I have no medical care, no place to live,” he said. “All of the things that I worked for all my life are gone.”

All of that over falsified evidence. “I contacted the Innocence Project in 2000 and it took them 16 years to get me out with extensive scientific evidence… that proved I was innocent,” Mr. Richards explained.

“I actually spent seven years in prison after a court ruled me innocent because they appealed and dragged it, and they came up with a technicality that you have seven people with doctorate degrees testifying to scientific evidence that it was not possible that I committed this crime,” he said. They countered that the experts “were only giving an opinion” on the DNA and everything else, that “that’s just opinion and it doesn’t matter.”

Finally in 2015, “they actually changed the law and said you can’t ignore expert testimony,” he said.

He finally got out in 2016, “but I came out broke with absolutely nothing.”

It took them four trials. He was ultimately convicted on bitemark testimony. “Even though we had proved that she had been dead hours before I got off work 46 miles away,” he explained. “They convinced the jury that this bite was mine, therefore, I was the one who bit her.”

However, as technology improved, they were able to re-examine the bitemark evidence with a computer, which found that the murderer’s mouth was half an inch wider and it couldn’t have possibly have been Mr. Richards’ bitemark.

He added, “We are here today because we’re not recognized. We go out the door, nobody knows us. The state doesn’t recognize us. We don’t even get $200 gate money. Parolees get gate money.

“It’s like go away, don’t bother us,” he said.

For the last year and a half, Mr. Richards has been staying with one of his attorneys. As he put it, “I’m 68 years old with advanced cancer, and my records still reflect me as a felon.”

Zavion Johnson was freed last month because of questionable evidence in a shaken baby case in Sacramento. He had been serving 25 years to life in state prison at Vacaville.

He was convicted of second-degree murder in the 2001 death of his daughter, Nadia, who was four months old at the time. He was 18 at the time of his conviction.

“It’s easy to go to jail, but it’s hard to get out,” he said.

“Everyone says, what are you going to do,” he said. “I don’t know. I have inadequate skills. I’m a good learner, though.

“The system is broken,” he said.

Rick Walker, a speaker at the Vanguard’s 2015 event, was convicted of murder in 1992. “The co-defendant in my case was the actual murderer,” he said. “They didn’t have a case against me, so they needed him.

“He should have got the death penalty for this case,” Mr. Walker stated. “Instead he got 15 years to life to help them convict me of this crime. It wasn’t hard for them to convict me of this crime because (I was) a black man from East Palo Alto and if you remember, in 1992 East Palo Alto was the murder capital of the world, per capita. My case was going on during that time.”

He ended up spending 12 and a half years in state prison. He was released in 2003.

“I’m just thankful that I did have family who were concerned and there for me,” he said. “At this trial, they couldn’t even place me at the scene of the crime.

“No physical evidence against me, all they had was the actual perpetrator’s testimony that I was there,” he said.

The supervising district attorney and the prosecuting district attorney had a bet. “I never thought you could get Walker,” Mr. Walker explained the supervising attorney said. “Here’s your nickel.”

“They bet a nickel on my life,” he added.

In prison he developed health issues. “Now I’m a 62-year-old, unemployed man, with no source (of income),” he said. “The state does this. They’re the real perpetrators here.

“When you get convicted of something they did, you send them to prison for something they did,” he explained. “When you’re wrong, and the reason why these guys don’t get any money when they get out of prison is because the arrogance of the state of California – there is no statute on the books that says if we do something wrong, these are the statutes for how we receive that matter.”

They ended up giving him $100 a day, based on a law for over-sentencing. “This is the kind of thing that we all face,” he said.

Gloria Killian was wrongly convicted of masterminding the 1981 robbery and murder of an elderly man, and was exonerated in 2002 with the help of astronaut Sally Ride’s mother. She had been convicted and sentenced to 32 years to life based on the evidence of a man who was already convicted in the crime and despite the fact that she had been arrested previously but the charges had been dismissed.

The informant was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life without parole. He immediately contacted the Sacramento County Sheriff’s Department to try to make a deal. He implicated Ms. Killian and in 1986 she was convicted. The informant’s sentence was vacated at the request of the prosecution.

“It was about ten years before I was able to get any help,” she said.

Even after being exonerated, “I remained in prison for four and a half months, because the Sacramento District Attorney’s Office did everything they could to make sure I could not be released from prison.”

She was eventually released on $250,000 bail.

“I had no money, I had no family,” she said. “I was ordered released in Los Angeles County, where I knew nobody. Because I got so much publicity, everything that I was given, was given to me by a total stranger who read or heard about me and said I want to help you.

“But I was lucky,” she said. “Because I did get a lot of support.”

While she described people as kind and generous, the state of California was not. “They continued to harass me for another ten years,” she said. Her DA was brought up on charges and censured for his conduct in this case.

“Right now, I’m a little bit scared,” she said. She was doing well a year ago, but her health has deteriorated in the last year following a collapse. She then had a heart attack. The stress has gotten to her and now she faces homelessness.

Right now she is living with a 95-year-old friend, to whom she is obligated for the help given to her.

“There are a lot of people to whom I am obligated,” she said. “The state of California is not one of them.”

The six individuals plus Ronnie Sandoval, mother of Arthur Carmona, who spoke on behalf of her son who was exonerated but died ten years ago in a traffic fatality, were speaking out to get the legislature to change the way that exonerated inmates are treated post-release. Much attention has focused on getting those individuals freed, but not enough to what happens when they are.

—David M. Greenwald reporting