Conservatives for weeks were convinced that there was going to be a Romney landslide, or at least victory, based on a bunch of flawed assumptions and a final decision that when science tells you something that you don’t want to hear, the science is wrong – which has some serious implications for climate change at the very least.

Conservatives for weeks were convinced that there was going to be a Romney landslide, or at least victory, based on a bunch of flawed assumptions and a final decision that when science tells you something that you don’t want to hear, the science is wrong – which has some serious implications for climate change at the very least.

In turns out we can reasonably predict even close elections based on careful polling. But some did not want to believe it. After all, they would convince themselves that the economy is horrible, that President Obama was to blame for the economy, and the public would see it their way if they just repeated themselves enough.

When the polling told them they were wrong, the obvious explanation was that the polling was wrong. That gets me to Dean Chambers, who might have been the anti-Nate Silver to the point where he had to apologize for belittling Nate Silver.

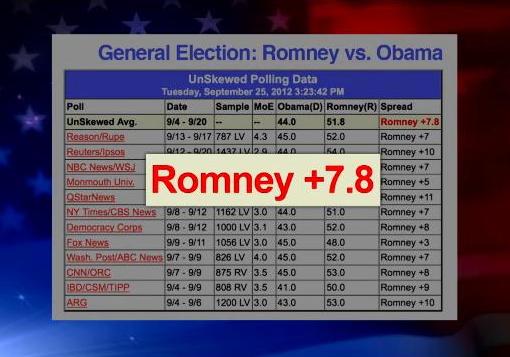

Mr. Chambers, a self-described internet journalist and commentator, launched a site this year called “UnskewedPolls.com.”

He explains the concept behind “unskewing” the polls: “The notion on which the polls were said to be ‘skewed’ was the calculation or projection that the turnout on Election Day would be something like 35 percent each of Democrats and Republicans. So when a poll included a sample of 44 percent Democrats and 38 percent Republicans, it was said to be skewed by six percent Democrats and the percentages were re-weighted for something like 35 percent of each and then the calculations lead to the ‘unskewed’ results.”

To his credit he writes something of a mea culpa, admitting, “What I was wrong on was the concept that the voter turnout would show something close to even in percentages of Democrats and Republicans who actually voted in the election.”

It sounds good, except that he’s actually 100% wrong as to why his prediction and, indeed, the premise of his site was completely off. What he’s wrong about is the idea that you can or should attempt to predict the distribution of partisan turnout.

In theory, the reason why the pollsters allow party ID to float is that party ID is not nearly the static concept we would like it to be. By fixing party ID, we first of all assume we know what the distribution should be and second we believe we can predict what Election Day voter turnout is going to be.

These are bad assumption and they also unnecessary.

Republicans, for the most part, believed that the voter turnout would look like 2004 where the parties turned out in even numbers and the Republicans were able to win a narrow victory. In fact, the voter map that Karl Rove envisioned looked a lot like 2004 except he gave Obama New Mexico and Nevada (two states that have clearly moved to the left in recent elections).

But why do all of this when you can allow your polling to do it for you?

Most pollsters create a random sample. They then look at the demographic breakdown of that sample. If it is significantly off they will weight their sample to reflect the demographic breakdown of the country according to the last census.

Based on that, they ask questions ascertaining people’s inclination to vote.

For the most part, those models got it right.

It turns out there were two factors at work. First, Democrats turned out in larger numbers than Republicans expected. Second, a lot of Republicans, for whatever reason, identified themselves as Independents – a lot of these were Tea Party affiliated voters – and they voted for the Republicans but called themselves Independents.

Republicans took a lot of solace in the Rasmussen Poll, along with Gallup. But both polls turned out to be among the worst and least reliable. Rasmussen made several errors – most critically they weighted their poll results and they only polled land lines, missing completely perhaps 30 percent of the electorate which was about 10 percent more Democratic affiliated than Republican affiliated.

The odd thing is that the idea of weighting party ID has been debated for years – the last time it came up was in 2004 when a lot of surveys showing Bush with the lead had heavily skewed samples. However, it turns out that those polls were picking up on something real and Bush in fact won, just as the polls suggested he would.

In October, the National Journal asked their panel of “political insiders” where, what I was wrong on, was the concept that the voter turnout would show something close to even in percentages of Democrats and Republicans who actually voted in the election.

Surprisingly, “Sixty-four percent of Democratic and Republican Insiders, including majorities in both parties, said polls should weight by party ID. Republicans on the whole felt stronger about siding with party identification, with 76 percent of them answering that way. Just over half, 51 percent, of Democrats agreed.”

Even political scientists, who should know better, could not agree.

The Wall Street Journal in early October interviewed political scientists on both sides of the issue.

“I don’t believe that weighting by party identification is necessary or advisable,” said John Sides, a political scientist at George Washington University. “The overall balance of party identification in the electorate can fluctuate. There is no steady baseline against which to weight.”

“The short-term variability in party ID is coming mostly, I believe, from people who have relatively low levels of interest in politics, knowledge about politics and are probably not particularly ideological in their political views,” said Scott Keeter, director of survey research at the Pew Research Center in Washington, D.C. “They tend to be more reactive to events and short-term forces than people who are more engaged in politics or more ideological.”

“Weak and leaning partisans, who are less stable than strong partisans, will sometimes break for the other party,” said Paul Goren, a political scientist at the University of Minnesota.

“Party identification moves with changes in presidential popularity and the state of ratings of the opposition party,” said Samuel Popkin, a political scientist at the University of California, San Diego.

But not all agree. Donald Green, for example, argued, “If you saw a poll with an unusually high dollop of Democrats, you would conclude that the Obama percentage is likely to be overstated.”

Instead, he suggested that using some reference point for party-ID breakdowns could improve the poll accuracy, even if such data are flawed.

“Even a noisy signal is still very helpful,” he said.

It would be interesting to see a re-interview after the election proved the floating models correct.

The lesson in all of this is that when you don’t get the results you expect or want, that does not mean the metrics are bad – it may be more likely that you were wrong.

I have a problem when people, who are essentially laymen when it comes to statistical modeling and polling, want to interject themselves and suggest that the professionals are wrong.

Professionals do get things wrong, but more often than not they learn from their mistakes and avoid repeating them.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

Silver and the other accurate poll aggregators use the same technique, conditional probability; the chance that an even occurs given other events or conditions (Google probability, jump to conditional). Today, with quick computers, the best way to calculate conditional probability is with Bayesian methods. Mr. Chambers could have quickly checked his proposition by calculating previous outcomes of elections based upon polls conditioned on his ratio of R/D. Silver and the other aggregators have looked at all possible conditionings, even Mr Chamber’s R/D, I assure you. If Mr. Chambers had been correct, the R/D conditioning would have been in the aggregators’ “posterior” probabilities. These “posteriors” are what Silver, Princeton, and the rest published. The right detested them because they predicted a blue win.

Been reading the national comments, and am quite surprised at howRomney and crew sincerely believed until Ohio turned blue that he was going to win big with independents, and Obama was going to have a low turnout.

Talk about assumptions …

All that money, and the flock of sheep just followed one or two guys over the assumption cliff

The Republicans, as a political party, have hung their hat on the fact that religion is more important than science for their world view. From creationism to the nuclear family (Strong Daddy and subservient Mommy and children) to human consciousness beginning at conception to denying climate science. Their treatment of Nate Silver is totally consistent with how they view analytical thought.