It is always hard to know how outside consultants will turn out, but the presentation by Bob Leland on the city’s Financial Forecasting Model was exceptional – it was rigorous, but explained in simple and easy to understand terms.

It is always hard to know how outside consultants will turn out, but the presentation by Bob Leland on the city’s Financial Forecasting Model was exceptional – it was rigorous, but explained in simple and easy to understand terms.

While most of the presentation served to reinforce things that the Vanguard has been reporting on for the last decade, the portion of the discussion on the tripling of pension costs was nonetheless nothing short of stunning.

As the mayor, Robb Davis, put it, “I knew the PERS stuff was going to be bad.” He said, “I’m kind of speechless on the percentage of some the (figures) – it’s really high…” He added, “It’s troubling.”

Perspective is needed on the mayor’s comments. Last December, he told the Vanguard that the unfunded liabilities situation was “urgent.” He said that, despite cost-containment and other efforts by the city, an actuarial report shows a huge jump in the city’s unfunded liabilities for pensions, among other things.

As he concluded at that time, “it is not clear to me at this point how we are going to cover everything over the next five years, given that we are not even covering critical infrastructure backlogs now.”

So, for him to be blown away and left “speechless,” given his level of concern four months ago, is rather remarkable, and yet I find myself in the same boat.

The mayor, in his response to the Vanguard, added, “After last evening’s presentation on the new projection model, I find it hard not to be concerned about the direction of pension, medical and retiree medical costs. They will continue to consume an ever-larger proportion of the budget in the coming years and there appears to be little we can do to change that. These costs will act as a fundamental constraint on our ability to fund critical infrastructure and program needs.”

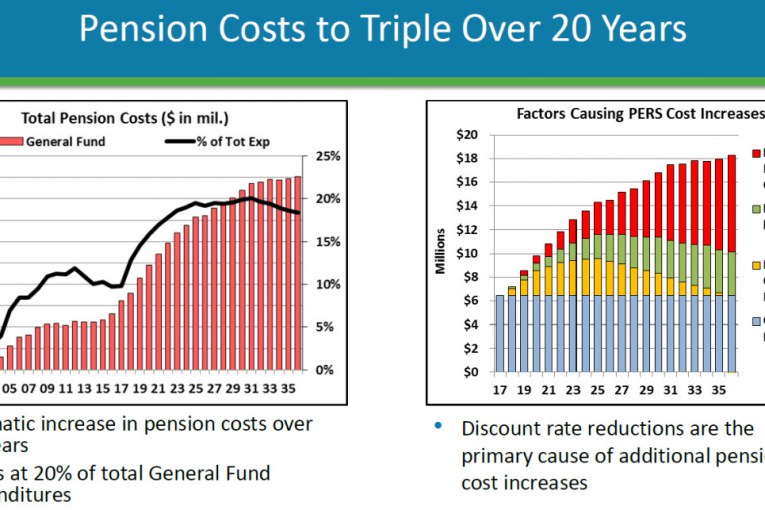

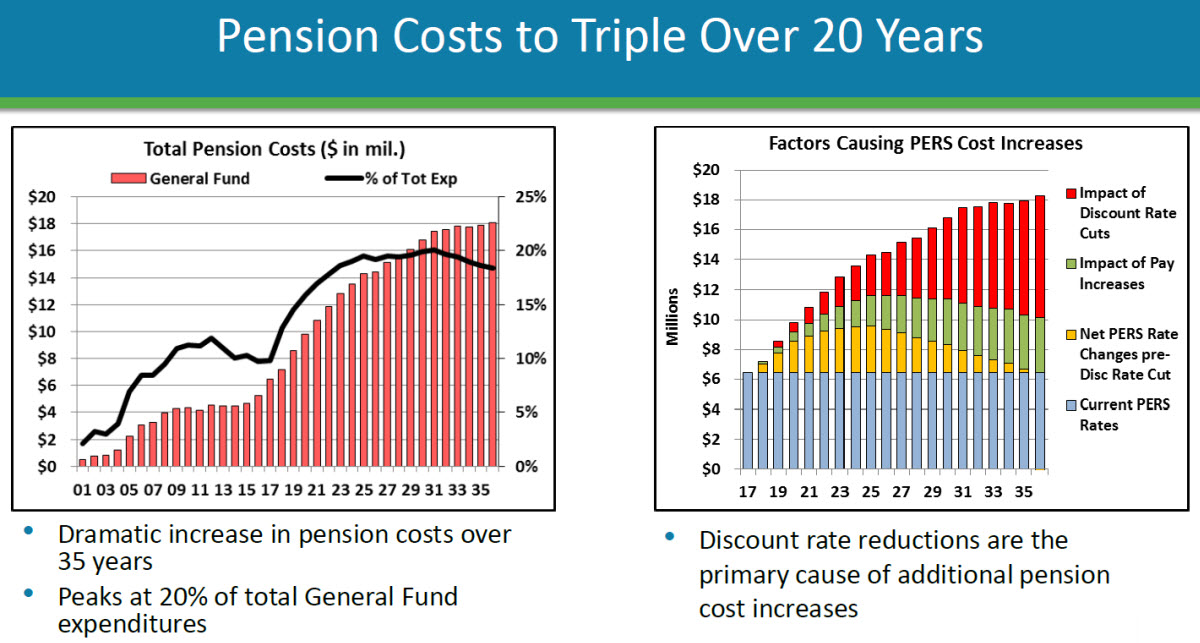

Mr. Leland found that pension costs are expected to TRIPLE over the next 20 years, going from about $6 million up to $18 million. He noted, “The rates started to escalate (following the dot-com bust), so rates that had been under $500,000 a year grew to about $4 million a year. In 2017, $6 million a year. That six million dollars is going to triple in twenty years. We have to be prepared for that.”

The pension hit alone will peak at 20 percent of total General Fund expenditures. To put this into perspective, in 2014, former City Manager Steve Pinkerton was concerned that pensions and OPEB (Other Post-Employment Benefits) would eat up one-quarter of the budget.

Now, pensions alone are expected to do that, with another 22 percent of payroll going to retiree medical.

And that figure could be worse.

The standard measure of health insurance, the Kaiser-Single Monthly Premiums, shows that from 2001 to 2017, costs have increased 249 percent or a compounded rate of 8.1 percent. That’s during a time when inflation was only about 2 to 2.5 percent per year.

There is now great uncertainty because it is unknown right now what is going to happen with federal health care. The graph from Mr. Leland’s presentation shows that the huge rate of health insurance growth hit a little bump around 2013 as the Affordable Care Act kicked in and started reducing or slowing the growth of premiums.

Right now, OPEB is projected to be only about 34 percent funded as of June 30, 2017, with gradual funding improvement over time. Contributions will be at 22 percent of payroll for the next 20 years. That means more than one-fifth of payroll is going for medical benefits for retirees.

But the hammer is the pension hit, which, again, is expected to triple.

It is important to understand where this came from and where this is going. In 2000, the pension fund, fueled by the dot-com boom, was “superfunded” and the municipalities were literally not paying for their pension funds.

Several factors would end up changing this. First, the dot-com bust led to a loss of state money. But municipalities would end up greatly ramping up not only pension rates but also salaries – each step would generate unfunded liabilities due to how pensions are structured.

When pension rates go up, they not only go up for the future, they are also retroactively applied. So if I have worked for 20 years at 2.5 percent at 60 and suddenly the council increases the formula to 3 percent – I get three percent for each of those twenty years despite the fact I was only paying into it at 2.5 percent.

The other problem is that the pension rate is calculated based on final salary. That led to problems such as spiking, but a more normal problem is the fact that if I retire at say $120,000 a year, but my average salary was only $80,000, I have been paying in at $80,000 but cash out at $120,000 – which again creates an unfunded liability to the city.

While it is easy to blame the whole system – the reality is that, at each step of the way, the Davis City Council enacted policies that greatly contributed to the problem.

In 2000, the city was not paying into PERS (Public Employees’ Retirement System), but that changed based on an action the council took in November of 2000.

On November 15, 2000, a city council comprised of Susie Boyd, Sheryl Freeman, Sue Greenwald, Michael Harrington and Mayor Ken Wagstaff, and led by Interim City Manager Jeanie Hippler, who took over for John Meyer, would approve a contract amendment to grant the firefighters a 3 percent at 50 pension compensation.

However, even at that time, in a document from August 23, 2000, the city disclosed that the change in the present value of benefits was $2.47 million, including an unfunded liability of $1.87 million.

That problem was compounded by exponential salary increases from 2000 to 2007. In 2004, the firefighters got an aggregated total of a 36 percent salary increase. The other bargaining units also got between 15 and 20 percent increases, which greatly increased the city’s obligations for pensions even though they had not funded them previously.

By 2008, according to the graph, the city, right before the Great Recession, owed $4 million annually for pensions.

The Vanguard in 2008 was warning that the pension system for the city was unsustainable. However, despite this, the city was slow to enact reform. In fact, the 2009 round of negotiations resulted in almost no change in the city policy. The city dealt with the downturn through attrition of employees, as well as putting infrastructure and other needs into an off-line budget category of “unmet needs.”

The city finally started to deal with pensions and other structural issues in the 2012-14 round of budget negotiations. However, by this point, it was clear at the state level that the pension system was overestimating its return on investment (ROI) and, in the process of reducing their expectations, pension increases went up to $6 million per year presently.

What Mr. Leland’s model now shows is that the bubble is about to completely burst – just as we’ve been warning for a decade – and the costs are about to go from $6 million (which is, again, 12 times what it was in 2001) up to $18 million by 2035.

This was entirely predictable back in 2008 – but, even knowing this was coming, the presentation by Bob Leland was stunning. The question now is what can and will the city do to change this.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

embed for Vanguard:

Let’s not forget SB 400 from 1999, which allowed all Tier 2 to elect Tier 1. I was the beneficiary of that law. I worked in the CalPERS legal office during the late 90’s when everyone was caught up in the stock market rally. I recall being happy to move into Tier 1 but wondering if the system wasn’t over-valued (which it was) and whether this wouldn’t cause problems down the line (which it did).

Perhaps it would help to explain what “Tier 1” and “Tier 2” are. I’m sure that a lot of Davis citizens have no idea what these terms mean.

Those terms (Tier 1/2) apply to State employees… not Davis employees. “Teir 1/Tier 2”, options do not apply (never has) for Davis employees… perhaps Leanna can elaborate, as to State…

There are, for City employees, 3% @ 50 for public safety, different formula (2.7% @ 57, if first hired after Jan 1, 2013 (State law reduction, plus state requirement that employees pay 1/2 half of the “normal contribution”)… 2.5% @ 55 for miscellaneous (2% @ 62, if first hired after Jan 1, 2013 (State law reduction, plus state requirement that employees pay 1/2 half of the “normal contribution”)

For verification/details, see : http://cityofdavis.org/city-hall/human-resources/memorandums-of-understanding-mous

Seems like the waters have been “muddied” by Leanna’s comment… UC retirement system, “local” PERS systems, State PERS, CalSTRS, all have different parameters, different benefits… different costs and different ‘unfunded liabilities’… the least funded ones are the UC and CalSTRS (DJUSD participates in that) systems

4 things:

1. Undertake a comprehensive review of staffing needs and adjust numbers and assignments accordingly.

2. Bring staff compensation levels — accounting for both salary and benefits — into line with those of the private sector.

3. Generate additional revenue. Raise new taxes and increase returns from existing taxes through business growth.

4. Cut services. I put this one last because the voters may not want to cut any more services, but it’s the savings source of last resort. If revenues can’t be increased, services will have to be cut, along with the staff that administer them.

My comment wasn’t so much about the city directly, but about how SB 400 impacted state pension liability and, indirectly, led to unions requesting and getting similar retirement formula improvements at the municipal level.

Here is a great explanation from the LA Times:

http://www.latimes.com/projects/la-me-pension-crisis-davis-deal/

“davis” in the link is Governor Davis, who now regrets signing SB 400. I knew Ron Seeling, the CalPERS chief actuary at the time. Ron was totally right.

Leanna is still muddying the waters here. SB400, while it affected only state employees, did not have that much impact on county and city employee groups. It was, in fact, exactly the other way around and negotiated as an attempt to catch up with local agencies that were hiring employees away from state service using relatively more generous pension plans and often higher salaries for comparable work descriptions. I am speaking here mainly of so-called miscellaneous employees, not the so-called badge units (fire, police, etc.) and since then, most state employees have rolled back the provisions of SB400 under Jerry Brown’s administration to 2.0 at 60 where it was prior to SB400.

Pension plans are delayed compensation. Pensions in the public sector have repeatedly been offered and sweetened by public entities as a way of avoiding higher salaries for the mass of rank and file employees. In essence, “we’re sorry we can’t afford to pay you more, but we can pay you later when and if you stay with us and retire.” This is the point that public entities need to focus on as they attempt to balance compensation with the fact that it is all paid for by taxpayers including the employees who are taxpayers themselves. It is unconscionable for an employer to offer a level of compensation that they either cannot or have no intention of honoring. The courts have so far agreed. It is akin to not paying full compensation at the end of the week or month.

It has always been my impression that local pensions have been richer than state ones because the distance between employee and employer are closer at the local level and thus there has been a desire to making people you are in contact with every day a little happier. Unions will negotiate and help get this under control if the picture is clearly presented (as in the case of state employees a few years ago) and there is some trust established.