In the wake of a series of high profile police incidents, Davis, like many cities across the nation, has purchased and implemented a body worn camera policy for the police. But what we are seeing is that there are limitations to those policies.

In the course of our investigation into local police practices, we learned of a case where a man, upon being arrested, was allegedly punched by Davis police officers. In one case, the officer testified in court that his body camera was not working.

The jury had the foresight to ask the officer if he checked the camera before leaving the station. The answer was yes. Was it working then? The answer was yes. But moments later at the scene of the incident, the body camera conveniently stopped working?

This is not an isolated incident. The Sacramento Bee reports over the weekend that body camera footage from a February 25 Rocklin shooting was made available showing “the tense moments following the fatal shooting of a 23-year-old Sacramento man by three Rocklin police officers in February.”

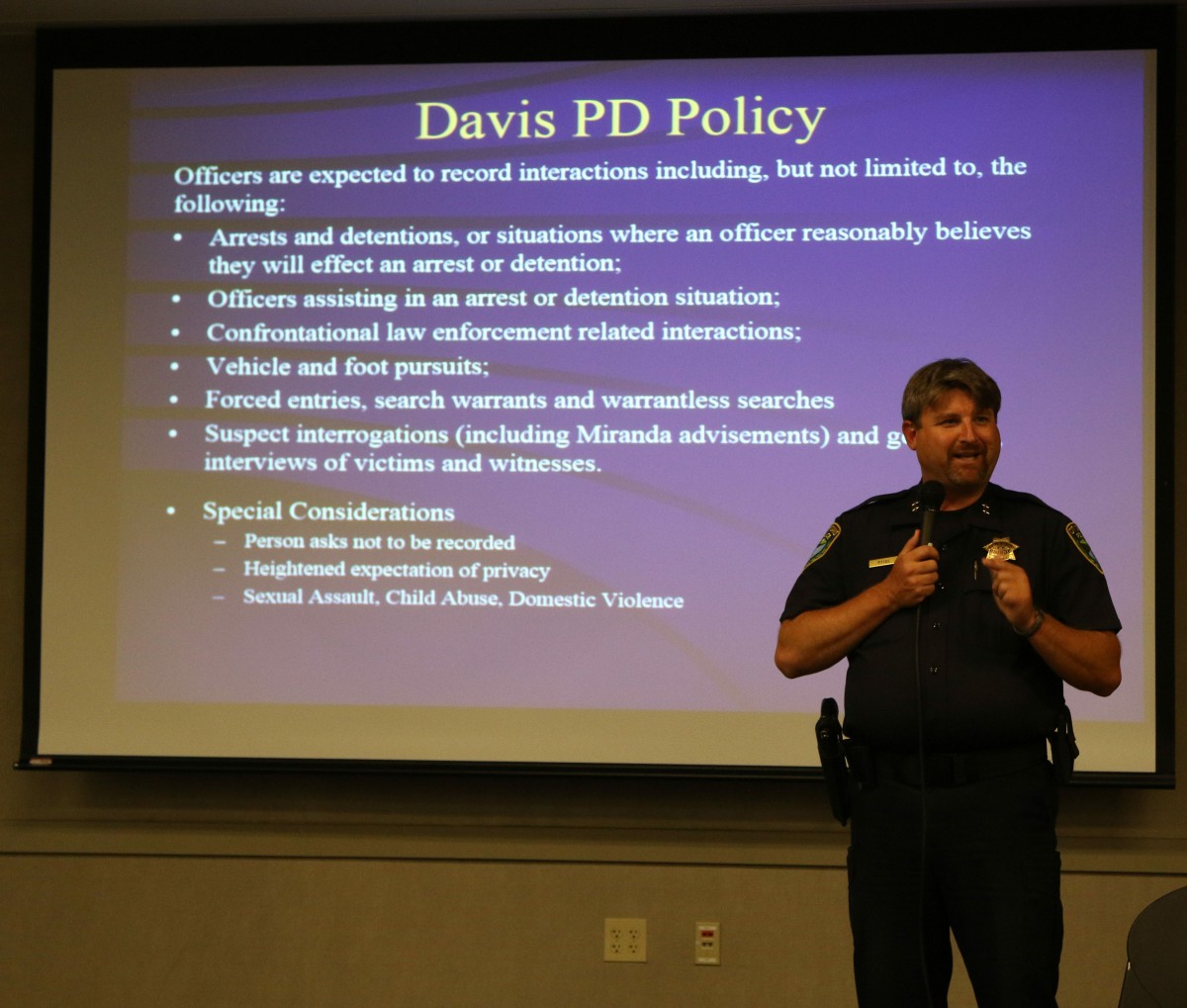

The Bee however reports: “None of the officers turned on the cameras until after the shooting, though department protocol is to activate them in most instances, including stops, pursuits or when they believe they may make an arrest or detain someone. Officers are not expected to jeopardize their safety to activate the cameras, the policy says.”

Naturally this was less than helpful, as the family attorney, Kellan Patterson, made clear to the Bee. The three officers were cleared in April of any criminal wrongdoing.

“Their release didn’t really do much to answer the question that was pertinent,” Patterson said. “Any objective information that existed about whether deadly force was necessary was not recorded because the officers neglected to turn on their cameras.”

Officers had several minutes to turn on their cameras before arriving to the scene, he said.

Radley Balko, columnist for the Washington Post, pointed out last week that “we’ve emphasized over and over that the public benefit to outfitting cops with body cameras will only be as good as the rules governing their use.”

He said, “Unfortunately, many state legislators and policymakers are reacting to the ‘war on cops’ narrative by giving all the control to police agencies. That isn’t a recipe for accountability.”

Here’s a good roundup at the Verge:

North Carolina, for example, passed legislation last year excluding body camera video from the public record, so footage is not available through North Carolina’s Public Records Act. That means civilians have no right to view police recordings in the Tar Heel state unless their voice or image was captured in the video.

Louisiana also exempts body camera video from public records laws.

South Carolina will only release body camera footage to criminal defendants and the subjects of recordings.

Kansas classifies body camera video as “criminal investigation documents” available only when investigations are closed . . .

In Pennsylvania, the state Senate recently passed Senate bill 560, which would mirror North Carolina’s opaqueness, and allow police to record inside civilian homes without restriction. It just passed the state House.

In Massachusetts, bill S. 1307 would mandate that body camera video “be kept confidential absent a court order.” It has been referred to the state Senate’s Joint Committee on Public Safety and Homeland Security.

Arkansas legislators made a smart decision by letting HB 1248 — a bill that would have made body camera video a “confidential record” — die in the state house, at least for now. If Arkansas residents — and citizens all over the country — don’t pay attention, it’s likely that bills like this one will reemerge. Then not only will body camera footage strengthen the surveillance state and fuel facial recognition and predictive policing systems, it’ll also be impossible for civilians to view it — which, for civilians, is the primary reason body cameras made sense in the first place.

A lot of these limitations apply here in Davis as well. For example, body camera video is subject to the Public Records Act, but the problem is that police records of this sort fall into the investigation record exemption, and they remain confidential to the public even after the investigation closes.

So when I made my request for the city’s video back in May, the response was “the Davis Police Department has an on-going investigation report and several video recordings. However, the records you requested are exempt from disclosure under the Public Records Act as an investigation record.”

Moreover, based on a 2002 case law, “The investigation exemption does not terminate when the investigation terminates.”

Of course, notwithstanding this objection, “The City has determined, however, that limited disclosure is necessary at this time to facilitate the City’s investigation of the incident. The City will disclose one of the videos in hopes of identifying additional witnesses to the incident.”

Mr. Balko points out “the New York Times recently reported that some police agencies have been preemptively releasing footage that depicts police officers performing brave and heroic deeds.”

Mr. Balko notes, “That’s fine. They should. But once you have policies that let law enforcement agencies highlight their best while essentially barring the press and watchdogs from holding accountable their worst, a promising transparency tool becomes little more than a tool for propaganda. And that isn’t going to win much trust between cops and the communities they serve.”

So how does one get video from the Davis Police Department? The policy lays out that it has to come out through a court process – either in a criminal trial or a civilian lawsuit.

And there is another problem that has come up time and time again – the police officers have to activate the cameras and this is by design, because there are legitimate concerns about privacy and certain incidents will not be videoed.

The problem with that is it gives police officers discretion. The best part of dash cams is that they are always recording. When the officers hit their lights, it starts saving the footage going back in time a few minutes so that the incident can be captured without the discretion of the police.

This doesn’t happen here with regard to the body cameras.

The ACLU notes: “Purely from an accountability perspective, the ideal policy for body-worn cameras would be for continuous recording throughout a police officer’s shift, eliminating any possibility that an officer could evade the recording of abuses committed on duty.

“The problem is that continuous recording raises many thorny privacy issues, for the public as well as for officers.” They argue, “Continuous recording would also mean a lot of mass surveillance of citizens’ ordinary activities.”

They argue the need for balance “to ensure that officers can’t manipulate the video record, while also placing reasonable limits on recording in order to protect privacy.”

When a police officer assigned to wear a body camera fails to record or otherwise interferes with camera video, three responses should result:

- Direct disciplinary action against the individual officer.

- The adoption of rebuttable evidentiary presumptions in favor of criminal defendants who claim exculpatory evidence was not captured or was destroyed.

- The adoption of rebuttable evidentiary presumptions on behalf of civil plaintiffs suing the government, police department and/or officers for damages based on police misconduct. The presumptions should be rebuttable by other, contrary evidence or by proof of exigent circumstances that made compliance impossible.

As Davis looks into a new police oversight system, it should do an audit of the body camera policy to see how well it is working and what can be done to improve it.

—David M. Greenwald reporting

I have a couple of questions about procedure that would seem pertinent to some of the stated issues:

1. Wondering why there is not a uniform time when a camera should be activated, for instance the moment a dispatch call is received ? The time of the call would be the reference point for compliance, no subjective discretion needed.

2. In the case of a spontaneous stop, why not an automatic camera turn on as officer exits the car ?

3. With regard to privacy concerns, I am not sure I fully understand this. Why not have a sworn officer whose duty it is to delete material that is incidentally captured and might be sensitive rather than missing events that might not reflect favorably on police action ?

I think the first important answer to the why nots is part of the answer is that this is new and therefore they are still figuring out best practices.

The problem I see with (3) is that then you end up with subjective judgments and give someone in the agency an ability to delete footage. While I am sympathetic to the ACLU privacy concerns, at this point my bigger concern is with what isn’t getting videoed than what is getting videoed.

3. is indeed the problematic one… it is NOT the sworn officer’s duty to delete material “incidentally captured”… quite the contrary, as I believe David is pointing out.

The real danger is if all ‘material’ is deemed “public record”… some would say “it all is”… that would help sell papers, get hits on blogs. But a line officer should not delete anything recorded. But not all of what is recorded should be publicly accessible, even via a PRA request. Particularly not to regular or social “media”. That should be a decision by management, with assistance from legal counsel.

Interestingly, we have no way of knowing whether some of the ‘third-party’ captures of events were “truncated” or otherwise manipulated before they were “released”. I’d treat those as ‘hearsay’ unless they were vetted by experts.

The body cam technology vs. privacy vs. ‘transparency’/public right to know, appears to be a very sticky wicket at this point.

But, not surprising…

Equally off-point… have a pet peeve about ‘tag lines’… the “you agree?” baiting. 95% of the time, that line is meant to provoke/tweak.

Don’t you agree, Jim?

It’s evening, and fish often rise to the bait around sundown…