On a July morning in 1967, when city crews striped a new lane down 3rd street, they invented a new form of American street. Those first bike lanes didn’t just change a college town—they gave future city planners a template.

From the first bike lanes to the nations’ first protected intersection nearly five decades later, Davis turned experiments into standards that spread through California manuals and into U.S. guidebooks. For anyone trying to understand or build bike culture, Davis is a near-perfect specimen of how it forms and grows, a model cities around the world can study if they want a truly bike-friendly atmosphere.

History of cycling in Davis

Davis is a small, flat, tree-lined university town located in Northern California with an approximate width of 5.5-6.0 miles and an approximate length of 4.0-4.5 miles. As of 2020, the city’s population was 66,850. The adjacent campus of UC Davis has about 15000 residents as of 2024. Weather in Davis can be characterized by hot, dry summers and mild wetter winters which, along with the city’s flat topography, make it suitable for cycling.

- Pre 1964 and a campus catalyst

Davis has been known as “The Bicycle Capital of America” since early 1960s, but the history of cycling dates back even more. The California Aggie, Volume XXXIII, Number 16, 2 May 1940, reported a new Davis City ordinance requiring bicycle licenses—the kind of rule you pass only when a considerable amount of people were biking. In Department of Chemistry History from UC Davis, it noted that when the new chemistry building was dedicated on March 12, 1966, despite allowing parking, most of the Chemistry faculty still lived close-by and could bicycle to campus—a quiet but convincing evidence showing popularity of bike travel before 1960s. Direct evidence is hard to find due to length of time, but these lively pieces of words all suggested a wide usage of bike in Davis before 1960s.

California Aggie, Volume XXXIII, Number 16, 2 May 1940

In 1959, UC Davis was elevated from the farm campus of UC Berkely to a separate university under the UC system. Emil Mrak, who himself was a bike enthusiast, became the first chancellor of UC Davis. Seeing rapid enrollment growth on the horizon, Mrak turned cycling into a design mandate: in 1961 he told planners to “plan for a bicycle-riding, tree-lined campus.” That brief was merged into the 1963 Long Range Development Plan—calling for wide bike paths on and around campus (with undercrossings beneath major city roads), a largely car-free academic area, clear separation of bikes from cars and pedestrians, and sufficient racks near every building entrance. He reinforced the bike culture by sending out an invitation encouraging incoming students to bring bicycles so that everyday riding became the default on campus.

- 1964-1967: Opening the policy window

In early 1960s, cycling conditions deteriorated in Davis, as auto traffic increased, it became more dangerous for cyclists on roads. More cars on streets pushed bikes onto sidewalks, and bikes on sidewalks disrupted pedestrians. Something needed to be done to rebalance the friction between cyclists, motorists, and pedestrians.

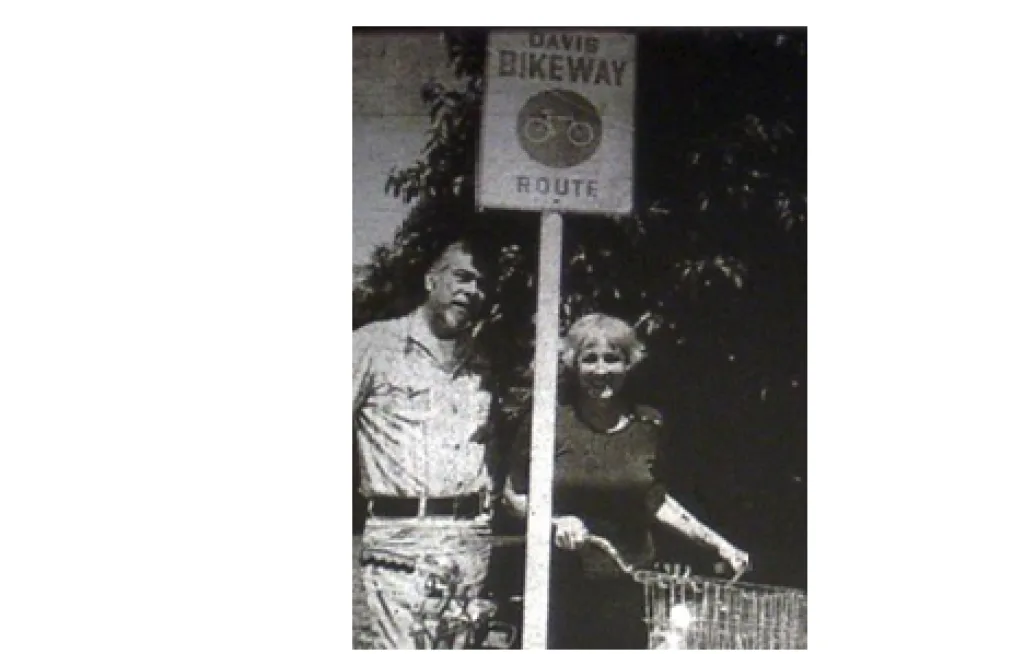

In 1964, when Frank and Eve Child returned from a four-month trip to Holland, they wrote a letter to the Davis Enterprise. In the letter, Childs pointed out the deterioration of biking conditions and the need to reform. Childs then presented the lifestyle he and his family enjoyed in Holland where they would bike wherever they needed to go. Next, Childs proposed the idea of painting bike lanes on city streets to provide a dedicated right of road for cyclists.

Frank and Eve Child

The Childs soon convened the Citizens’ Bicycle Study Group to proceed the letter into fruition. Although their first proposal to city council was turned down, the group created a petition that collected 533 signatures by December 14, 1964 and presented the proposal to city council once again. The result was not ideal either as only routes to elementary schools were agreed to be studied.

By 1966, the number of signatures climbed to 2000 as city council election approached. Pro bike lane candidates won in a landslide and, within months, the new council instructed Public Works to create bike lanes on arterial roads. Advocates worked with city staff to set the geometric standard for bike lanes.

The next step was to change The California Vehicle Code to recognize bikes as vehicles, therefore legalizing bike lanes as road elements. Luckily, Norm Woodbury, a council member, had connections with lobbyists at the State capital. City staff were able to make the right contacts to get the bill through the assembly and eventually signed by Governor Ronald Reagan.

In fall, 1967, the first bike lane in Davis and the U.S. was opened on Third St. through downtown and Sycamore Drive from Russell Blvd to 8th St. Bike lanes were clearly successful. Motorists enjoyed having cyclists out of their way, and cyclists enjoyed their designated lane on streets. The momentum didn’t just stop there. Also in 1967, UC Davis campus closed core campus to cars, leaving the campus to bikes and pedestrians.

Third Street Bike Lane, the first bike lane in Davis and the U.S.

- 1967-1972: Invention and Perfection

In 1971, students of UC Davis formed the Bike Barn, which provided a facility for students to receive assistance with their bikes. The bike barn provided students with a convenient and cheaper alternative to get their bikes fixed on campus.

Unlike in the city, roads in the campus experienced “rush hour” in between class schedules. When students were rushing from one lecture hall to another on their bikes, intersections soon became overwhelmed. In May 1972, a roundabout was created with fire hose laid out in the middle of Hutchison Drive and California Ave intersection. Cyclists were instructed to go clockwise until reaching their exit. The roundabout ultimately turned out to be a success at improving safety and ease of navigation in intersections.

Bike Roundabout in UC Davis Campus outside Rock Hall

In early 1970s, most bike policies governing the city were set and standardized. The city seemed to have reached the point of “nowhere to innovate.”

Beyond History

History explains how Davis became the first American city to paint bike lanes and experiment with roundabouts. But history doesn’t ride a bike—people do. Behind every policy was a city planner, a school official, an advocate, or a daily commuter who believed bicycles were more than a two-wheeled vehicle. To understand how cycling in Davis moved beyond infrastructure into culture, we turn to the stories of those who made it happen.

One of those people is David Takemoto-Weerts, whose own story mirrors the rise of cycling in Davis. As a freshman at UC Santa Cruz in the late 1960s, he had no car, just a 10-speed bicycle to climb the hills between classrooms. A single ride with upperclassmen into mountains changed everything for David. ‘That one day ride just kind of got me hooked on a bicycle,’ David recalled. ‘It was no longer just transportation. It was liberating.’ When he moved to Davis in 1971, he found a city already filled with bicycles.

David joined the newly-opened Bike Barn in his second year, calling it “the best job I ever had.” It was more than a repair shop; it was a community hub where students learned by doing. “There was a camaraderie between the students working there,” he said. “Even the management were students. It became the focal point for campus cyclists.” At a time when the only bike shops in town were a Schwinn dealer and a lawnmower shop, the Bike Barn provided a critical, and cheaper alternative for students to seek assistance with their bikes.

Carrying on with the passion for bikes, David later spent three decades as UC Davis’s Campus Bicycle Coordinator, where his influence reached every corner of campus. In late 1980s, David worked to replace the concrete “bike pods” that could easily bent wheels of bikes. Although bent wheels brought extra business to Bike Barn when he was working there. “I knew they were inferior and not good for a lot of things,” David recalled. He began searching catalogs and testing designs. The breakthrough came with the “lightning bolt” racks. “We put a couple out in a busy area to see how people used them,” David recalled. “Everybody loved them.”

Concrete bike pods (top) and “lightning bolt” rack (bottom) in UC Davis Campus

From there, the racks spread across campus, slowly replacing the old pods. Later, a Sacramento company introduced an improved version called the Varsity Dock, and David worked closely with the designers. “They’d bring me prototypes, ask for feedback, and we’d test them right on campus,” he said.

When architects showed David their plan for the new Social Sciences & Humanities Building, they insisted on installing wave racks because they looked stylish. David had to push back the decision. ‘When you look at campus on a nice spring day, you don’t see racks—you see bikes,’ he reminded them. “Forget the appearance. We need racks that work.”

David was on campus when the first bike roundabout was sketched with chalk and fire hoses outside Rock Hall. “When students arrived, they had no idea what to do with that thing,” he laughed. “But before, it was just chaos—people shooting through intersections, hoping for the best. The roundabout made it flow.”

The confusion that followed the installation soon became part of campus lore. “During the first week of fall quarter,” David recalled, “some of the fraternities would drag out lawn chairs and just sit there watching the crashes.” For students on bikes, the roundabout was a medium of passage, but for Davis cycling culture, it’s a symbol of how the city learned by doing. By the time David retired in 2017, there were 27 roundabouts on campus.

Apart from Design, David also led quiet efforts to accommodate bikes on the campus. Every year, hundreds of bikes were abandoned after students moved out. He supervised a crew of student workers—ten during the school year, four in the summer—whose job was to collect, catalog, and prepare the abandoned bikes for auction. “We picked up roughly a thousand bikes a year,” he recalled. “It was a never-ending job.” The abandoned bikes were sold twice a year, first through live auctions that drew hundreds of people, and later through online auctions. “Those bikes were part of the cycle of the campus,” David said.

In recent years, David began to worry about the rise of e-bikes and scooters. “They go fast, and you can’t hear them,” he warned. “You don’t hear them coming next to you, so sometimes they just flash through.” The mix of different speeds between e-bikes, traditional bikes, and pedestrians created new safety challenges that Davis hadn’t faced before.

To tackle these challenges, David believed that Davis needs to regain its focus on education, enforcement, and maintenance. David recalled how effective bike patrol officers had been when they rode through the city on bikes. “Having officers on bikes made a big difference,” he said. “They could actually talk to people, explain the rules, and keep things from getting out of hand, or just reminding cyclists to stop at stop signs.” David also stressed the urgent need to renovate the aging bike infrastructures in the city. “A lot of the pavements are in bad shape,” he said. “Sometimes you hit cracks or potholes that’ll throw you off your bike.”

Despite these frustrations, David remains hopeful that Davis can once again lead by example. “We were once ahead of everyone else,” he said. “But now other places have passed us. We need to reinvest: fix the roads, repaint the lanes, and bring back the pride in biking that we used to have.”

From Davis to the world

According to Susan Handy, professor in the Department of Environmental Science and Policy at the University of California at Davis, formation of bike culture requires a combination of attitude, perception, and infrastructure. Davis is a special case in which bike culture developed “bottom up”—people were used to riding bikes before infrastructures existed. However, in other places around the world, especially big cities, “top down” policy support would be needed to foster bike culture.

Personal attitude reflects how people view biking in general, whether as a practical way of travel, a form of leisure, or as a last resort choice. “People have to feel safe bicycling,” professor Handy said. People need to be convinced that it is safe and enjoyable out there on bikes. “Some people will always bike no matter what, but most people need to feel that it’s convenient and enjoyable. You have to make it something people actually want to do,” she added.

Social perception determines whether biking feels normal. In Davis, it is natural to show up to class or work by bike. Elsewhere, Professor Handy said, cities have used cultural events to shift perceptions. “You need programs that change behavior and culture, things like May Is Bike Month or open streets events. They help build the culture and change people’s individual attitudes.” Bogotá, capital of Columbia, opens major roads every Sunday and holidays from 7am to 2pm for its Ciclovía events, when major roads in the city are temporarily blocked to cars allowing cyclists to ride in a more comfortable environment. These events can help build the culture and change people’s attitudes.

The final, and probably the most straightforward element, is infrastructure. Without connected, protected network of bike paths, biking will never be truly safe. “A city can’t expect people to bike if the roads make them feel like they’re taking their life in their hands,” Professor Handy added.

In Davis, development of all three elements stemmed from community—students, city planners, and residents built a self-sustaining cycling culture. However, in larger cities where cars dominate and biking is still considered unconventional, such development would have to be fostered by deliberate policies.

Immediate questions people would ask when considering giving more room for bikes rather than cars are whether it is worth it, and what about efficiency of transport. Professor Handy pushed back against the idea that efficiency should be the only goal. “We tend to measure transportation success in terms of how many cars we can move and how fast,” she said. “But that’s not really what streets are for. The true goal should be to improve safety and livability for everyone.”

Professor Handy went on to explain the concept of road diet, which typically converts four-lane roads into three lanes with a bike lane. In real world practice, road diets often don’t reduce efficiency in the way people fear. Instead, they tend to make streets calmer and safer for all users. She emphasized that the benefits of road diets extend beyond cyclists. Lower speeds and fewer lanes reduce collisions, simplify intersections, and make neighborhoods more pleasant. “It’s safer, it’s quieter, and people actually like being on those streets more,” Professor Handy explained. She argued that city planners should see streets not just as corridors for vehicles, but as shared public spaces. “We should be asking who the streets are for,” she said. “They’re not just for moving cars, they’re for people.”

Davis itself has served as a model of road diet. The city reduced Fifth street from four lanes to two car lanes with a center turn lane and new bike lanes on both sides. “It didn’t slow down traffic, or maybe it’s okay to slow down cars a little bit. Because it’s improving safety for everyone—for people on bikes, for people walking, and even for drivers.” Professor Handy said.

Intersection on 5th Street and Pole Line Road in 2014 (top) and 2024 (down). Notice the bike lane painted in green.

Despite Davis’ long-standing reputation as the bike capital of United States, Professor Handy agreed with David that the city’s enthusiasm has dimmed. “I feel like we’re in kind of a lull in terms of Davis’ pride in biking,” she said. “We’re resting on our laurels.” She pointed out that local advocacy groups have lost momentum, and Davis must focus on basics like “fixing potholes, repainting bike lanes, keeping the infrastructure in shape.”

Still, Professor Handy sees Davis as a guide for the rest of the world. What began as an experiment in a small university town has become the framework for sustainable transportation everywhere. “Davis is a reminder that culture, policy, and design can work together. If you build the right infrastructure, support it with policy, and make biking feel normal, people will ride.”

Follow the Vanguard on Social Media – X, Instagram and Facebook. Subscribe the Vanguard News letters. To make a tax-deductible donation, please visit davisvanguard.org/donate or give directly through ActBlue. Your support will ensure that the vital work of the Vanguard continues.